Great Arabic Poets

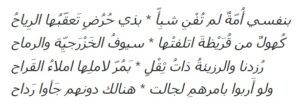

Sarah (fl. 6th-7th century) was born to the Jewish Banu Qurayza clan of the Arabian Peninsula, in the pre-Islamic era when much of the peninsula was inhabited by Jews. Her family originally hailed from what is today Yemen. They lived in Yathrib, the flourishing oasis of the Banu Qurayza Jews. In 622, Muhammad entered the city, and in 627 he annihilated the Banu Qurayza tribe (and renamed the city “Medina”, making it the first capital of the Islamic empire). Sarah was a poet, and one of her poems describing the devastation of Yathrib has survived. It was first printed in a 10th-century anthology of Arabic poems called Kitab al-Aghani. She wrote: “By my life, there is a people not long in Du Hurud; obliterated by the wind. Men of Qurayza destroyed by Khazraji swords and lances; We have lost, and our loss is so grave…” According to legend, she fought in the battle against Muhammad and was killed. (In a little-known quirk of history, Muhammad actually took two of the Jewish captives for himself as wives, and one of them is even considered a “mother of Islam”!) Incredibly, Sarah of Yemen may be history’s oldest and first known Arabic poet.

Another famous Jewish-Arab poet was Qasmuna bint Ismail (fl. 11th-12th century), who lived in Andalusia (today’s Spain). She was the child of a wealthy and well-educated Jew, who made sure his daughter was literate and taught her the art of poetry. Qasmuna is the only Sephardic Jewish female poet whose work has survived. Three of her poems were published in a 15th century anthology. In one of her poems she wrote: “Always grazing, here in this garden; I’m dark-eyed just like you, and lonely; We both live far from friends, forsaken; patiently bearing our fate’s decree.” In another she describes reaching the age of marriage and the struggle of finding the right partner: “I see an orchard, Where the time has come; For harvesting, But I do not see; A gardener reaching out a hand, Towards its fruits; Youth goes, vanishing; I wait alone, For somebody I do not wish to name.” She has also been referred to as “Qasmuna the Jewess” and “Xemone”.

Back When Palestinians Insisted There’s No Such Thing as Palestine

Words of the Week

In Judaism the word for “education” (chinukh) is the same as for “consecration”. Is your child being consecrated for a life of beneficence for Israel and humanity?

– Rabbi Dr. J.H. Hertz, former Chief Rabbi of Britain