The Persian Jew Who Inspired India

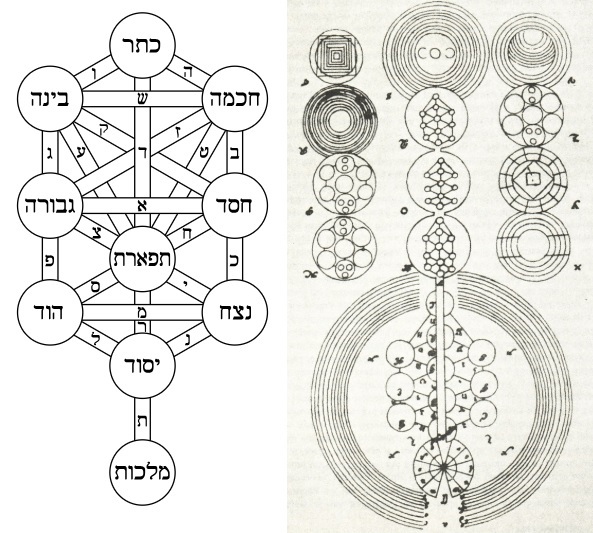

Sa’id Sarmad Kashani (c. 1590-1661) was born in Armenia to a religious Persian-Jewish family of merchants. At a young age, he translated the Torah into Farsi. He later took up studies under Muslim scholars and mystics like Mulla Sadra and Mir Findiriski. Some believe he nominally converted to Islam at this time, but remained a practicing Jew. On one merchant trip to Mughal India, Sarmad met a Hindu scholar called Abhay Chand. The two learned about each other’s faiths, and it is believed Chand converted to Judaism. Sarmad eventually gave up his wealth and became an ascetic wandering mystic. He and Chand traveled and taught together all across India, eventually settling in Delhi. Sarmad made a great name for himself as a poet and philosopher. Over 300 of his short poems have survived to this day. He also wrote the entry for “Judaism” in the 17th-century Dabistan, an anthology explaining all of the world’s religions. The Mughal crown prince Dara Shikoh (whose father built the Taj Mahal) was so impressed by Sarmad’s wisdom that he became a disciple, too. Sarmad went on to devise a new mystical system, drawing on Judaism, Sufi Islam, and Hinduism. Countless followers and disciples across India learned from him. However, when Dara Shikoh was deposed by his brother, the new Mughal emperor executed Shikoh and all of his associates, including Sarmad. The emperor demanded that Sarmad recite the Shahadah (proclaiming “there is no God but Allah and Muhammad is His prophet”), but Sarmad refused and was beheaded. According to legend, Sarmad then picked up his own head and walked away—and the new emperor never had a peaceful night’s sleep ever again! Sarmad’s tomb became a popular pilgrimage site and is still revered as a holy place in India today. His story inspired numerous Indian leaders, including Abul Kalam Azad, a colleague of Gandhi (and his predecessor as president of the Indian National Congress). Azad once described himself as a modern-day Sarmad. Scholars see “Sarmad the Jew” as a key figure in the history of religions; a mystic that influenced the development of Judaism, Islam, and Hinduism; as well as an early pioneer of interfaith dialogue.

Passover Begins Monday Night – Chag Sameach!

Secrets of the Ten Plagues & the Passover Seder

Words of the Week

In the chronicles of world history, no question has managed to capture the world’s interest for very long; a few decades seems to be the outer limit for consideration of even the most pressing global problems. But the world has been busy trying to figure out the question of the Jews for thousands of years – and they have not tired of the discussion! In every generation, the old questions arise anew: Are the Jews good or bad? Do the Jews bring benefit to the world or do they cause problems? Why, it is as if we have just appeared on the scene – as if the world has never before known what a Jew looks like!

– Rabbi Yerucham Levovitz (1875-1936)