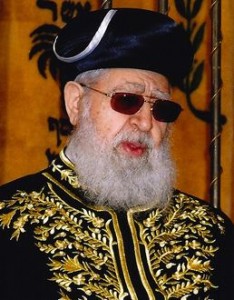

Yitzhak ben Zeev Diva (c. 1902-2008) was born in Baghdad to a rabbi who worked as a spice trader. Early on, he plunged into the depths of Jewish wisdom and by his teenage years was already recognized as a prodigy. In 1923, he settled in the Holy Land to bring spirituality into the secular Zionism that was flourishing in Israel. Upon arrival, he officially changed his last name to Kaduri. He continued his learning under some of the greatest rabbis of the time, particularly at Jerusalem’s famous Porat Yosef Yeshiva. Meanwhile, refusing to live on charity, he worked as a scribe and bookbinder, committing the books that he worked on to memory. It is said that he memorized the entire Talmud (over 5400 pages of dense text), together with its commentaries, along with a multitude of other works. He wrote several mystical texts of his own, which were never published, as Rav Kaduri did not want them getting into the wrong hands. He went on to become the head mekubal (“Kabbalist”) among Israel’s rabbis. His son spearheaded the opening of Rav Kaduri’s own yeshiva – Nachalat Yitzchak – located in the Bukharian Quarter of Jerusalem next to the Rav’s home. Rav Kaduri was famous for eating very little, and speaking very little. Despite his occupation with study, his doors were always open to help others (in fact, he refused to lock the doors of his home even amidst a spate of thefts). Hundreds of people sought his advice and blessings each day, and he was known as a miracle worker and healer. At his funeral, 8 years yesterday, over 300,000 people came to pay their respects.

Words of the Week

When God created the first man, He showed him all the trees of the Garden of Eden, and said to him: ‘See My works, how beautiful and praiseworthy they are. And everything that I created, I created for you. Be careful not to spoil or destroy My world—for if you do, there will be nobody after you to repair it.’

– Midrash Kohelet Rabbah 7:13