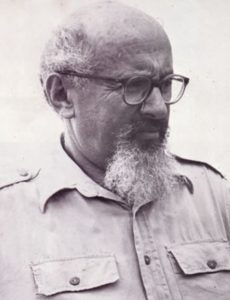

Pediatrician, Oligarch, Philanthropist

Mikhael Mirilashvili (b. 1960) was born to a Jewish family in Kulashi, Georgia. He moved to St. Petersburg at 17 to study mathematics, then switched to medicine and became a pediatrician. As many new opportunities opened up with the collapse of the Soviet Union, Mirilashvili went into business. He started with real estate, then expanded to retail stores, banking, television, oil and gas, and casinos. He owned six casinos in St. Petersburg alone, and his Viking bank is among the city’s most popular. Mirilashvili was a cofounder of Russian social media app Vkontakte, which he sold in 2013 for $1.12 billion. In 2000, his father was kidnapped by a group of criminals posing as police officers. Two weeks after his father’s release, the kidnappers were all found dead. Mirilashvili was arrested for ordering the hit on his father’s captors, and spent eight years in prison. Upon his release in 2009, he moved to Israel and has since invested a great deal in the country, including in Israel’s new offshore gas fields. He is a generous philanthropist, donating millions to ZAKA (of which he was chairman), Keren haYesod, Yad Vashem, the IDF, the World Jewish Congress, the Russian Jewish Congress (of which he is the vice-president), the Torah and Chessed Center for Georgian Jews, as well as Migdal Ohr, an organization started by beloved rabbi Yitzchak Dovid Grossman (known as “the disco rabbi”) to help struggling Israeli youths. Mirilashvili’s funding has allowed Migdal Ohr to support, educate, and care for over 17,000 impoverished and disadvantaged Israeli kids and teens. Mirilashvili also co-founded and owns Watergen, an Israeli start-up that transforms air into clean drinking water, extracted and filtered from humidity. Watergen machines are now found in over one hundred water-starved regions of the world. In previous years, Mirilashvili donated seven such machines to the Gaza Strip, each providing over 2000 litres a day of clean water, powered by solar cells. The machines are still operating in the Gaza Strip amidst the war, providing essential water to Palestinians. Watergen machines are also operating in Ukraine, though Mirilashvili has been falsely accused by the Ukrainians of supporting the Russian invasion. He has dispelled these myths, and reminds people that he was imprisoned for years in a Russian jail, survived several Russian assassination attempts, and has sold off nearly all of his Russian-based businesses. Meanwhile, Mirilashvili established the Israeli-Emirati Water Research Institute in Abu Dhabi (together with Tel Aviv University), and the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Food Security at Ben-Gurion University in honour of his father. Over the years, he has donated millions more to synagogues, hospitals, and Jewish schools, for medical equipment, Torah scrolls, and ambulances, as well as a special fleet of firetrucks to combat forest fires in Israel.

“Jewish Awakening” Causes Global Shortage of Tefillin and Mezuzahs

Three Approaches to the Arab-Israeli Conflict from This Week’s Torah Parasha

Support the #KidnappedFromIsrael Campaign

Words of the Week

The Arab refugee problem was caused by a war of aggression, launched by the Arab States against Israel in 1947 and 1948. Let there be no mistake: If there had been no war against Israel, with its consequent harvest of bloodshed, misery, panic and flight, there would be no problem of Arab refugees today.

– Abba Eban