The Rabbi Who Launched Zionism

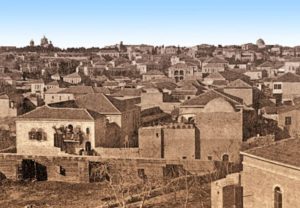

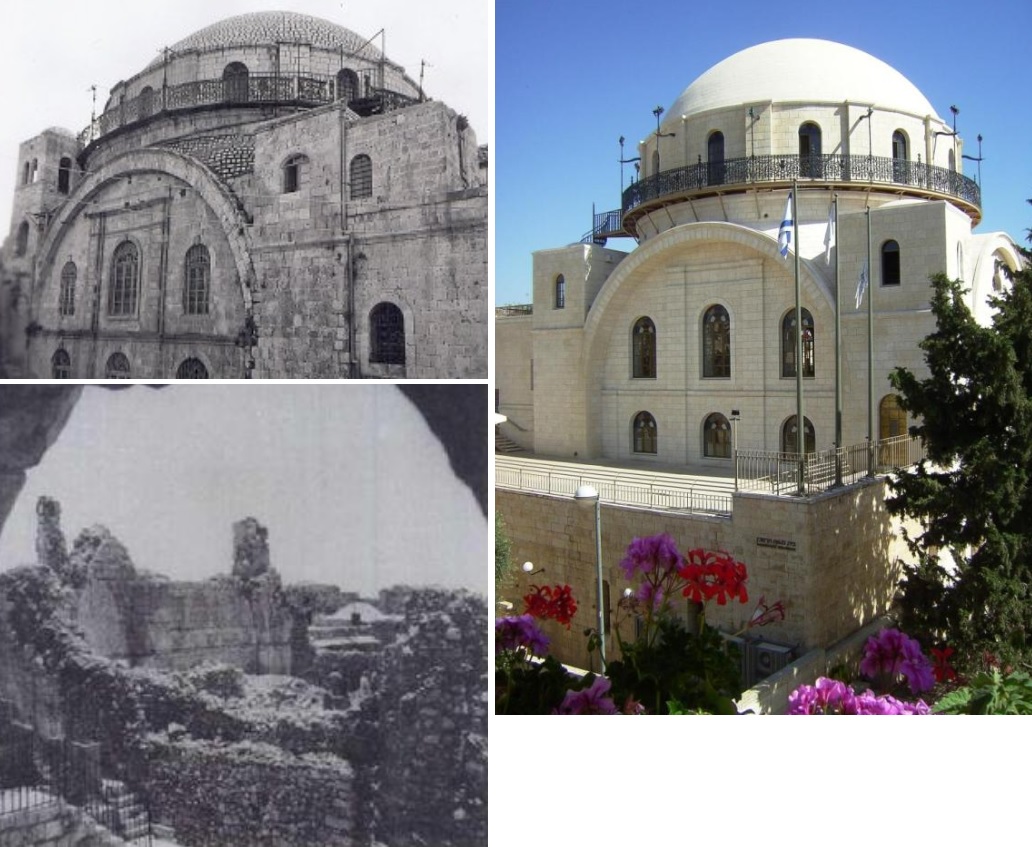

Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (1795-1874) was born in what was then Prussia (now Poland) to a long line of rabbis. After receiving his own rabbinic ordination and getting married, he moved to the city of Thorn and there served as the rabbi for over forty years. Incredibly, he never took a salary for this role, and instead made a living running a small business with his wife. He wrote commentaries on the Torah, Talmud, Passover Haggadah, and a wide range of topics in Jewish law. Meanwhile, Rabbi Kalischer was deeply concerned about the state of Jewry, both in Europe and in the Holy Land. He worried about the pogroms, persecutions, and poverty experienced by Jews in Eastern Europe, and equally worried about the mass-assimilation, secularism, and rise of Reform Judaism in Western Europe. Meanwhile, he wanted to make existing Jewish communities in places like Jerusalem, Hebron, Tiberias, and Tzfat flourish and become self-sufficient, instead of relying heavily on donations from abroad. For Rabbi Kalischer, the solution to all of these problems was Jewish nationalism, and he began writing on these issues in the Hebrew magazine HaLevanon. In 1862, he put his ideas together in a book titled Derishat Zion, and followed it up with Rishon L’Zion in 1864. He argued that Jews should come together to purchase land in Israel, build agricultural schools to teach farming and land management, and to establish a Jewish military force to protect the Jews of the Holy Land. He also hoped to re-establish the sacrifices and offerings in Jerusalem as specified in the Torah. Rabbi Kalischer argued that Jews should stop waiting for God to solve their problems: “One should not think that the Blessed One will suddenly descend from the Heavens to tell his people – ‘leave!’ – or that he will send His messenger any moment to call us on the trumpet…” While many critiqued this approach, Rabbi Kalischer defended his position with citations from all across Jewish holy texts. He went on speaking tours around Europe to spread the message, and convinced countless people to join the cause. Rabbi Kalischer was a key inspiration for prominent figures like Sir Moses Montefiore, Adolphe Crémieux, and Edmond de Rothschild. His work led directly to the establishment of the first agricultural school in the Holy Land in 1870, called Mikveh Israel. He even donated his own savings of 12,000 francs towards purchasing more land in Israel. Rabbi Kalischer is widely regarded as one of the early founders of Zionism.

Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (1795-1874) was born in what was then Prussia (now Poland) to a long line of rabbis. After receiving his own rabbinic ordination and getting married, he moved to the city of Thorn and there served as the rabbi for over forty years. Incredibly, he never took a salary for this role, and instead made a living running a small business with his wife. He wrote commentaries on the Torah, Talmud, Passover Haggadah, and a wide range of topics in Jewish law. Meanwhile, Rabbi Kalischer was deeply concerned about the state of Jewry, both in Europe and in the Holy Land. He worried about the pogroms, persecutions, and poverty experienced by Jews in Eastern Europe, and equally worried about the mass-assimilation, secularism, and rise of Reform Judaism in Western Europe. Meanwhile, he wanted to make existing Jewish communities in places like Jerusalem, Hebron, Tiberias, and Tzfat flourish and become self-sufficient, instead of relying heavily on donations from abroad. For Rabbi Kalischer, the solution to all of these problems was Jewish nationalism, and he began writing on these issues in the Hebrew magazine HaLevanon. In 1862, he put his ideas together in a book titled Derishat Zion, and followed it up with Rishon L’Zion in 1864. He argued that Jews should come together to purchase land in Israel, build agricultural schools to teach farming and land management, and to establish a Jewish military force to protect the Jews of the Holy Land. He also hoped to re-establish the sacrifices and offerings in Jerusalem as specified in the Torah. Rabbi Kalischer argued that Jews should stop waiting for God to solve their problems: “One should not think that the Blessed One will suddenly descend from the Heavens to tell his people – ‘leave!’ – or that he will send His messenger any moment to call us on the trumpet…” While many critiqued this approach, Rabbi Kalischer defended his position with citations from all across Jewish holy texts. He went on speaking tours around Europe to spread the message, and convinced countless people to join the cause. Rabbi Kalischer was a key inspiration for prominent figures like Sir Moses Montefiore, Adolphe Crémieux, and Edmond de Rothschild. His work led directly to the establishment of the first agricultural school in the Holy Land in 1870, called Mikveh Israel. He even donated his own savings of 12,000 francs towards purchasing more land in Israel. Rabbi Kalischer is widely regarded as one of the early founders of Zionism.

Torah Simulation Theory (Video)

Words of the Week

If whites are successful, it’s “white privilege”; if minorities are successful, it’s “empowerment”; if Jews are successful, it’s a conspiracy.

– Jon Stewart

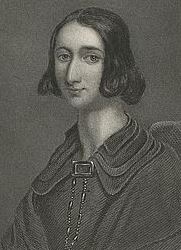

Grace Aguilar (1816-1847) was born in London to descendants of Sephardic Jewish refugees who fled the Portuguese Inquisition. Her parents were active leaders of London’s Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue. Grace was a sickly child, and seldom left her home for the first eight years of her life. During this time, she learned dance, piano and harp, and was tutored in Jewish studies and classical literature. She started writing at this time, too. As a teenager, her father taught her Hebrew and more advanced Jewish studies while she took care of him during a long bout with tuberculosis. She then took care of her ill mother, before being plagued with a serious case of measles starting at age 19. With her brothers away at boarding school, she bore the burden of caring for her parents and taking care of the family home. To raise more money, Aguilar strove to become a professional writer. Her first book, a collection of riddle-poems called The Magic Wreath of Hidden Flowers, was a huge success and launched her writing career. She then published a translation and explanation of an earlier Spanish work called Israel Defended, written to prevent Jews from converting to Christianity. Aguilar became good friends with future British prime minister (and former Jew of the Week)

Grace Aguilar (1816-1847) was born in London to descendants of Sephardic Jewish refugees who fled the Portuguese Inquisition. Her parents were active leaders of London’s Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue. Grace was a sickly child, and seldom left her home for the first eight years of her life. During this time, she learned dance, piano and harp, and was tutored in Jewish studies and classical literature. She started writing at this time, too. As a teenager, her father taught her Hebrew and more advanced Jewish studies while she took care of him during a long bout with tuberculosis. She then took care of her ill mother, before being plagued with a serious case of measles starting at age 19. With her brothers away at boarding school, she bore the burden of caring for her parents and taking care of the family home. To raise more money, Aguilar strove to become a professional writer. Her first book, a collection of riddle-poems called The Magic Wreath of Hidden Flowers, was a huge success and launched her writing career. She then published a translation and explanation of an earlier Spanish work called Israel Defended, written to prevent Jews from converting to Christianity. Aguilar became good friends with future British prime minister (and former Jew of the Week)