Defender of Judaism

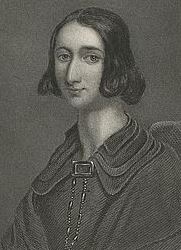

Grace Aguilar (1816-1847) was born in London to descendants of Sephardic Jewish refugees who fled the Portuguese Inquisition. Her parents were active leaders of London’s Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue. Grace was a sickly child, and seldom left her home for the first eight years of her life. During this time, she learned dance, piano and harp, and was tutored in Jewish studies and classical literature. She started writing at this time, too. As a teenager, her father taught her Hebrew and more advanced Jewish studies while she took care of him during a long bout with tuberculosis. She then took care of her ill mother, before being plagued with a serious case of measles starting at age 19. With her brothers away at boarding school, she bore the burden of caring for her parents and taking care of the family home. To raise more money, Aguilar strove to become a professional writer. Her first book, a collection of riddle-poems called The Magic Wreath of Hidden Flowers, was a huge success and launched her writing career. She then published a translation and explanation of an earlier Spanish work called Israel Defended, written to prevent Jews from converting to Christianity. Aguilar became good friends with future British prime minister (and former Jew of the Week) Benjamin Disraeli who helped her spread her writings. She soon convinced Isaac Leeser, editor of the popular Jewish magazine, The Occident, to publish her new book, The Spirit of Judaism, in 1842. The book was very popular both in America and England. Aguilar continued to write poetry, fiction, and treatises on Judaism. While she had become a bestseller, she still did not earn enough to care for her family, and had to work as a director of a Hebrew school. In 1845, Aguilar published Women of Israel, describing the lives of great Jewish women in history, and serving as an inspiration for countless Jewish women at the time. Some consider this to be her masterpiece. She followed that up with The Jewish Faith: Its Spiritual Consolation, Moral Guidance, and Immortal Hope, explaining the value and beauty of Judaism. Two years later, Aguilar was struck with spinal paralysis. She had already planned to set out on a trip to Europe, and refused to cancel it. She died in Frankfurt, and was buried in its Jewish cemetery. Her tombstone fittingly has verses from Eshet Chayil (“Woman of Valour”, from King Solomon’ Proverbs, chapter 31). Many more of Aguilar’s incredible works were published after her death, including collections of Jewish stories, novels for women, proto-Zionist writings, and works on Sephardic Jewish and English Jewish history. Her novel Home Influence, which had its first print just as Aguilar was dying, went on to sell out thirty editions. Her works were used as textbooks in some of the first American Hebrew schools. Although she was only 31 years old when she died, Aguilar is credited with being one of the most important Jewish educators and writers of her time, and playing a tremendous role in preventing Jews from assimilating and converting. Today, there is a public library named after her in New York City. Aguilar Point in British Columbia is named after her brother, who was an officer in the British Royal Navy. At her death, she was called “the moral governess of the Hebrew family”.

Grace Aguilar (1816-1847) was born in London to descendants of Sephardic Jewish refugees who fled the Portuguese Inquisition. Her parents were active leaders of London’s Spanish-Portuguese Synagogue. Grace was a sickly child, and seldom left her home for the first eight years of her life. During this time, she learned dance, piano and harp, and was tutored in Jewish studies and classical literature. She started writing at this time, too. As a teenager, her father taught her Hebrew and more advanced Jewish studies while she took care of him during a long bout with tuberculosis. She then took care of her ill mother, before being plagued with a serious case of measles starting at age 19. With her brothers away at boarding school, she bore the burden of caring for her parents and taking care of the family home. To raise more money, Aguilar strove to become a professional writer. Her first book, a collection of riddle-poems called The Magic Wreath of Hidden Flowers, was a huge success and launched her writing career. She then published a translation and explanation of an earlier Spanish work called Israel Defended, written to prevent Jews from converting to Christianity. Aguilar became good friends with future British prime minister (and former Jew of the Week) Benjamin Disraeli who helped her spread her writings. She soon convinced Isaac Leeser, editor of the popular Jewish magazine, The Occident, to publish her new book, The Spirit of Judaism, in 1842. The book was very popular both in America and England. Aguilar continued to write poetry, fiction, and treatises on Judaism. While she had become a bestseller, she still did not earn enough to care for her family, and had to work as a director of a Hebrew school. In 1845, Aguilar published Women of Israel, describing the lives of great Jewish women in history, and serving as an inspiration for countless Jewish women at the time. Some consider this to be her masterpiece. She followed that up with The Jewish Faith: Its Spiritual Consolation, Moral Guidance, and Immortal Hope, explaining the value and beauty of Judaism. Two years later, Aguilar was struck with spinal paralysis. She had already planned to set out on a trip to Europe, and refused to cancel it. She died in Frankfurt, and was buried in its Jewish cemetery. Her tombstone fittingly has verses from Eshet Chayil (“Woman of Valour”, from King Solomon’ Proverbs, chapter 31). Many more of Aguilar’s incredible works were published after her death, including collections of Jewish stories, novels for women, proto-Zionist writings, and works on Sephardic Jewish and English Jewish history. Her novel Home Influence, which had its first print just as Aguilar was dying, went on to sell out thirty editions. Her works were used as textbooks in some of the first American Hebrew schools. Although she was only 31 years old when she died, Aguilar is credited with being one of the most important Jewish educators and writers of her time, and playing a tremendous role in preventing Jews from assimilating and converting. Today, there is a public library named after her in New York City. Aguilar Point in British Columbia is named after her brother, who was an officer in the British Royal Navy. At her death, she was called “the moral governess of the Hebrew family”.

Words of the Week

There are rabbis who are so great that they can revive the dead. But reviving the dead is God’s business. A rabbi needs to be able to revive the living.

– Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, the Kotzker Rebbe