The French Abraham Lincoln

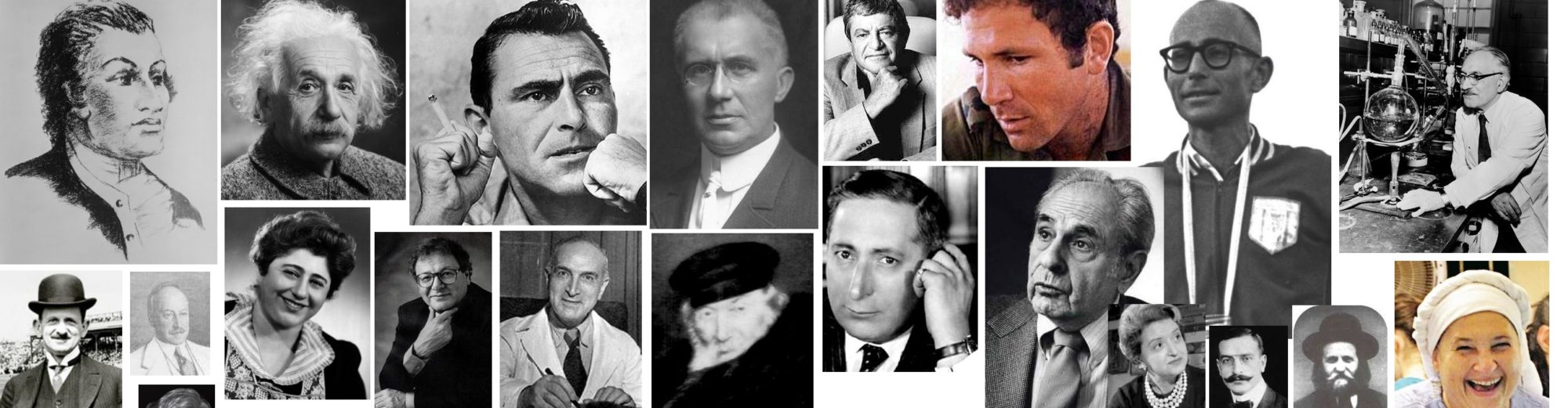

Isaac-Jacob Adolphe Crémieux (1796-1880) was born in Nimes, France to a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family. He became a lawyer and, following the Second French Revolution of 1830, moved to Paris to enter politics. In 1848, he was appointed minister of justice. One of his first acts was to abolish slavery in all French colonies, for which he has been called “the French Abraham Lincoln”. Crémieux was made a life senator in 1875. Meanwhile, he was always a passionate defender and advocate for the rights of Jews. In 1834, Crémieux became vice-president of the Central Consistory of the Jews of France, a role he held for the rest of his life. In 1860 he was co-founder of the Alliance Israelite Universelle, with a mission to protect Jewish rights and Jewish communities around the world, and a special mission to help impoverished Sephardic and Mizrachi Jewish communities across the Ottoman Empire. Crémieux served as president of the Alliance for nearly two decades. The Alliance was most famous for its top-notch schools (meant for Jews but open to all people), the first opening in Morocco in 1862, the second in Baghdad in 1864, and then a school in Jerusalem in 1868. Ironically, Haj Amin Al-Husseini, founder of the Palestinian Arab resistance (and terrorism) movement—a Nazi sympathizer and good friend of Adolf Hitler—studied at the Jerusalem Alliance school in his youth! In 1870, with permission from the Ottoman government, the Alliance started a network of agricultural schools in the Holy Land, going on to play an instrumental role in the Zionist movement and the establishment of the State of Israel. By 1900, the Alliance ran 101 schools with over 26,000 students across the Middle East and North Africa. Crémieux was famous for defending Jews around the world. When the Jews of Saratov, Russia were accused of a blood libel in 1866, he travelled to St. Petersburg to defend them, and won the case. In 1870, his “Crémieux Decree” finally granted citizenship to all Jews in Algeria. Today, there are streets named after him in Paris, Tel-Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem.

Isaac-Jacob Adolphe Crémieux (1796-1880) was born in Nimes, France to a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family. He became a lawyer and, following the Second French Revolution of 1830, moved to Paris to enter politics. In 1848, he was appointed minister of justice. One of his first acts was to abolish slavery in all French colonies, for which he has been called “the French Abraham Lincoln”. Crémieux was made a life senator in 1875. Meanwhile, he was always a passionate defender and advocate for the rights of Jews. In 1834, Crémieux became vice-president of the Central Consistory of the Jews of France, a role he held for the rest of his life. In 1860 he was co-founder of the Alliance Israelite Universelle, with a mission to protect Jewish rights and Jewish communities around the world, and a special mission to help impoverished Sephardic and Mizrachi Jewish communities across the Ottoman Empire. Crémieux served as president of the Alliance for nearly two decades. The Alliance was most famous for its top-notch schools (meant for Jews but open to all people), the first opening in Morocco in 1862, the second in Baghdad in 1864, and then a school in Jerusalem in 1868. Ironically, Haj Amin Al-Husseini, founder of the Palestinian Arab resistance (and terrorism) movement—a Nazi sympathizer and good friend of Adolf Hitler—studied at the Jerusalem Alliance school in his youth! In 1870, with permission from the Ottoman government, the Alliance started a network of agricultural schools in the Holy Land, going on to play an instrumental role in the Zionist movement and the establishment of the State of Israel. By 1900, the Alliance ran 101 schools with over 26,000 students across the Middle East and North Africa. Crémieux was famous for defending Jews around the world. When the Jews of Saratov, Russia were accused of a blood libel in 1866, he travelled to St. Petersburg to defend them, and won the case. In 1870, his “Crémieux Decree” finally granted citizenship to all Jews in Algeria. Today, there are streets named after him in Paris, Tel-Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem.

From Gaza Mosque to IDF Soldier

Why the Dome of the Rock is the Perfect Monument to Islam

The Spiritual Significance of the Coming Solar Eclipse

Words of the Week

Human life is undoubtedly a supreme value in Judaism, as expressed both in Halacha and the prophetic ethic. This refers not only to Jews, but to all men created in the image of God.

– Rabbi Shlomo Goren

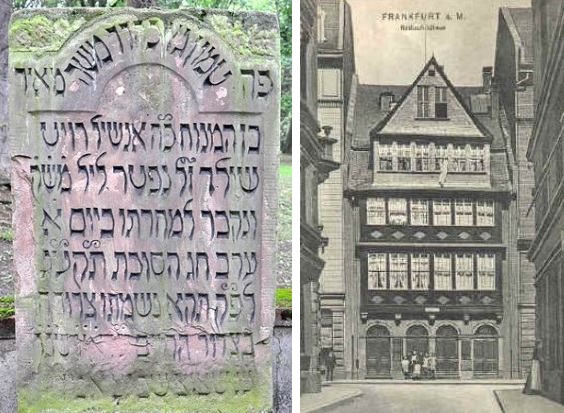

Mayer ben Anshel Rothschild (1744-1812) was born in the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt. His father was a merchant and dabbled in currency exchange. The family had lived in the same house of the Frankfurt ghetto for over a century; a house with a red sign above the door. The family would thus become known as Rothschild meaning “red sign”, referring to that first house, even when they later moved to another property in the ghetto. Although his father wanted him to become a rabbi, Mayer Rothschild became an apprentice of Simon Wolf Oppenheimer, a banker and “Court Jew”. (Some say Mayer had to leave his rabbinic studies after his parents died.) From Oppenheimer he learned the financial business, and become a dealer of rare coins. This brought him into the court of the Prince of Hesse (a duchy within pre-Germany’s “Holy Roman Empire”). By 1785, Rothschild had become one of the Prince’s main bankers. The French Revolution erupted just a few years later, and Britain would handle its hiring of Hessian mercenaries in the conflict through Rothschild. This made Rothschild quite wealthy, and at the turn of the 19th century, he began loaning money internationally. This business was facilitated by the help of his five sons: Nathan in London, Jacob in Paris, Salomon in Vienna, Kalman in Naples, and the eldest son Amschel taking over in Frankfurt. As the family prospered and entered into the nobility, they adopted a coat of arms, the simpler version of which features a red shield with five arrows to represent the five sons (based on the words of Kings David and Solomon in Psalm 127: “Like arrows in the hand of a warrior, so are the children of one’s youth”), and a motto: concordia, integritas, industria, “Unity, Integrity, Diligence”. Mayer Rothschild also had five daughters, and instilled in all ten of his children the importance of maintaining Jewish values. Unlike other wealthy European Jews, the Rothschilds did not assimilate, intermarry, or convert to Christianity. They played a central role in easing the plight of Europe’s Jews, and later in the establishment of the State of Israel. They would amass the largest private fortune in modern history, and possibly of all time. As per Jewish tradition, Mayer and his five sons were generous philanthropists. The Rothschild model of a tightly-controlled family business, with multiple branches established by siblings, inspired many other successful banks and companies, both Jewish and gentile. Mayer Rothschild himself has been described as the “founding father of international finance”, and ranked by Forbes among history’s most influential businesspeople. Next week we will explore the lives and achievements of his sons.

Mayer ben Anshel Rothschild (1744-1812) was born in the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt. His father was a merchant and dabbled in currency exchange. The family had lived in the same house of the Frankfurt ghetto for over a century; a house with a red sign above the door. The family would thus become known as Rothschild meaning “red sign”, referring to that first house, even when they later moved to another property in the ghetto. Although his father wanted him to become a rabbi, Mayer Rothschild became an apprentice of Simon Wolf Oppenheimer, a banker and “Court Jew”. (Some say Mayer had to leave his rabbinic studies after his parents died.) From Oppenheimer he learned the financial business, and become a dealer of rare coins. This brought him into the court of the Prince of Hesse (a duchy within pre-Germany’s “Holy Roman Empire”). By 1785, Rothschild had become one of the Prince’s main bankers. The French Revolution erupted just a few years later, and Britain would handle its hiring of Hessian mercenaries in the conflict through Rothschild. This made Rothschild quite wealthy, and at the turn of the 19th century, he began loaning money internationally. This business was facilitated by the help of his five sons: Nathan in London, Jacob in Paris, Salomon in Vienna, Kalman in Naples, and the eldest son Amschel taking over in Frankfurt. As the family prospered and entered into the nobility, they adopted a coat of arms, the simpler version of which features a red shield with five arrows to represent the five sons (based on the words of Kings David and Solomon in Psalm 127: “Like arrows in the hand of a warrior, so are the children of one’s youth”), and a motto: concordia, integritas, industria, “Unity, Integrity, Diligence”. Mayer Rothschild also had five daughters, and instilled in all ten of his children the importance of maintaining Jewish values. Unlike other wealthy European Jews, the Rothschilds did not assimilate, intermarry, or convert to Christianity. They played a central role in easing the plight of Europe’s Jews, and later in the establishment of the State of Israel. They would amass the largest private fortune in modern history, and possibly of all time. As per Jewish tradition, Mayer and his five sons were generous philanthropists. The Rothschild model of a tightly-controlled family business, with multiple branches established by siblings, inspired many other successful banks and companies, both Jewish and gentile. Mayer Rothschild himself has been described as the “founding father of international finance”, and ranked by Forbes among history’s most influential businesspeople. Next week we will explore the lives and achievements of his sons.