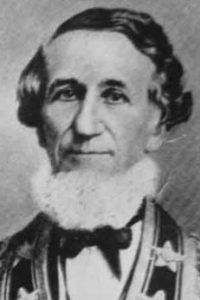

The French Abraham Lincoln

Isaac-Jacob Adolphe Crémieux (1796-1880) was born in Nimes, France to a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family. He became a lawyer and, following the Second French Revolution of 1830, moved to Paris to enter politics. In 1848, he was appointed minister of justice. One of his first acts was to abolish slavery in all French colonies, for which he has been called “the French Abraham Lincoln”. Crémieux was made a life senator in 1875. Meanwhile, he was always a passionate defender and advocate for the rights of Jews. In 1834, Crémieux became vice-president of the Central Consistory of the Jews of France, a role he held for the rest of his life. In 1860 he was co-founder of the Alliance Israelite Universelle, with a mission to protect Jewish rights and Jewish communities around the world, and a special mission to help impoverished Sephardic and Mizrachi Jewish communities across the Ottoman Empire. Crémieux served as president of the Alliance for nearly two decades. The Alliance was most famous for its top-notch schools (meant for Jews but open to all people), the first opening in Morocco in 1862, the second in Baghdad in 1864, and then a school in Jerusalem in 1868. Ironically, Haj Amin Al-Husseini, founder of the Palestinian Arab resistance (and terrorism) movement—a Nazi sympathizer and good friend of Adolf Hitler—studied at the Jerusalem Alliance school in his youth! In 1870, with permission from the Ottoman government, the Alliance started a network of agricultural schools in the Holy Land, going on to play an instrumental role in the Zionist movement and the establishment of the State of Israel. By 1900, the Alliance ran 101 schools with over 26,000 students across the Middle East and North Africa. Crémieux was famous for defending Jews around the world. When the Jews of Saratov, Russia were accused of a blood libel in 1866, he travelled to St. Petersburg to defend them, and won the case. In 1870, his “Crémieux Decree” finally granted citizenship to all Jews in Algeria. Today, there are streets named after him in Paris, Tel-Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem.

Isaac-Jacob Adolphe Crémieux (1796-1880) was born in Nimes, France to a wealthy Sephardic Jewish family. He became a lawyer and, following the Second French Revolution of 1830, moved to Paris to enter politics. In 1848, he was appointed minister of justice. One of his first acts was to abolish slavery in all French colonies, for which he has been called “the French Abraham Lincoln”. Crémieux was made a life senator in 1875. Meanwhile, he was always a passionate defender and advocate for the rights of Jews. In 1834, Crémieux became vice-president of the Central Consistory of the Jews of France, a role he held for the rest of his life. In 1860 he was co-founder of the Alliance Israelite Universelle, with a mission to protect Jewish rights and Jewish communities around the world, and a special mission to help impoverished Sephardic and Mizrachi Jewish communities across the Ottoman Empire. Crémieux served as president of the Alliance for nearly two decades. The Alliance was most famous for its top-notch schools (meant for Jews but open to all people), the first opening in Morocco in 1862, the second in Baghdad in 1864, and then a school in Jerusalem in 1868. Ironically, Haj Amin Al-Husseini, founder of the Palestinian Arab resistance (and terrorism) movement—a Nazi sympathizer and good friend of Adolf Hitler—studied at the Jerusalem Alliance school in his youth! In 1870, with permission from the Ottoman government, the Alliance started a network of agricultural schools in the Holy Land, going on to play an instrumental role in the Zionist movement and the establishment of the State of Israel. By 1900, the Alliance ran 101 schools with over 26,000 students across the Middle East and North Africa. Crémieux was famous for defending Jews around the world. When the Jews of Saratov, Russia were accused of a blood libel in 1866, he travelled to St. Petersburg to defend them, and won the case. In 1870, his “Crémieux Decree” finally granted citizenship to all Jews in Algeria. Today, there are streets named after him in Paris, Tel-Aviv, Haifa, and Jerusalem.

From Gaza Mosque to IDF Soldier

Why the Dome of the Rock is the Perfect Monument to Islam

The Spiritual Significance of the Coming Solar Eclipse

Words of the Week

Human life is undoubtedly a supreme value in Judaism, as expressed both in Halacha and the prophetic ethic. This refers not only to Jews, but to all men created in the image of God.

– Rabbi Shlomo Goren

Abraham Jonas (1801-1864) was born in England to a religious Jewish family. He moved with his brothers to Cincinnati in 1819, and they were the first Jewish family to journey west to the new frontier beyond the Allegheny Mountains. They were also the founders of the first synagogue in Ohio, Congregation B’nai Israel. Jonas married Lucy Seixas, the daughter of

Abraham Jonas (1801-1864) was born in England to a religious Jewish family. He moved with his brothers to Cincinnati in 1819, and they were the first Jewish family to journey west to the new frontier beyond the Allegheny Mountains. They were also the founders of the first synagogue in Ohio, Congregation B’nai Israel. Jonas married Lucy Seixas, the daughter of