First Jew (and Scientist) in America

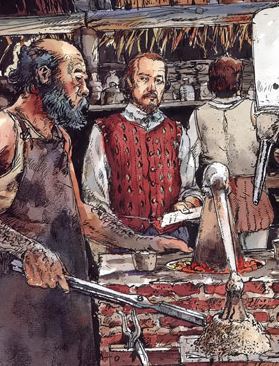

Illustration of Joachim Gans and Thomas Hariot in America’s First Science Lab (Credit: National Park Service)

Joachim Chaim Gans (later known as Dougham or Yougham Gannes) was born in the thriving Jewish community of 16th-century Prague, then the capital of the Kingdom of Bohemia. Nothing is known of his early life. Historical records show that Gans was invited to England in 1581 to demonstrate his mining and smelting techniques. Gans had invented a new, cheaper method for purifying copper, reducing the length of the process from sixteen or eighteen weeks to just four. He also developed new ways of producing sulfuric acid, vitriol, and other compounds, most notably saltpeter (for gunpowder). “Master Yougham” was soon a respected scientist in the court of Queen Elizabeth I. When Sir Walter Raleigh was given a royal charter to explore the New World in 1584, he hired Gans as the expedition’s chief metallurgist. Gans’ primary objective was discovering valuable metals in the New World, and to determine whether further exploration and settlement was worthwhile. Gans set forth on the voyage, and in 1585, was one of the founders of Roanoke, England’s first colony in America. Amazingly, archaeologists have uncovered Gans’ original laboratory, filled with mining tools and scientific instruments. His team (together with Thomas Hariot) discovered many new plants, mapped the surrounding landscape, and even identified sassafras as a treatment for syphilis. Most importantly, Gans determined that the New World contains ample amounts of iron and copper, and perhaps silver and gold, too, convincing the queen that the continent was worth investing in. Gans himself is credited with being the first Jew to set foot in North America, as well as its first technologist or materials scientist. His lab has been called “America’s First Science Center” and “the Birthplace of American Science”. Unfortunately, the first colony didn’t last long, and 104 of the original 108 settlers, including Gans, returned to England a year later. Gans settled in Bristol and continued his work for the Royal Mining Company. When it became known that he spoke Hebrew and Yiddish, the town reverend asked Gans if he denied “Jesus Christ to be the son of God.” Gans replied: “What needeth the almighty God to have a son? Is He not almighty?” Gans was subsequently arrested for blasphemy. He was sent to London to be tried by the Queen’s Privy Council. What happened after this is unclear. There are no further records of Gans. Many historians hold that he was spared the death penalty because of his tremendous contributions to England, and was instead deported. There is mention of a “Joachim Gantz” buying a large estate 80 kilometres north of Prague in 1596, not far from a mine. It is quite likely that he lived out the rest of his life quietly in his homeland. Scholars believe Joachim Gans is the basis for the character Joabin, the wise scientist and “good Jew” of Sir Francis Bacon’s famous 1627 novel New Atlantis. Last Friday, the state of North Carolina (where Roanoke was located) officially honoured Gans in a ceremony, and will soon erect a commemorative highway marker for him near Fort Raleigh.

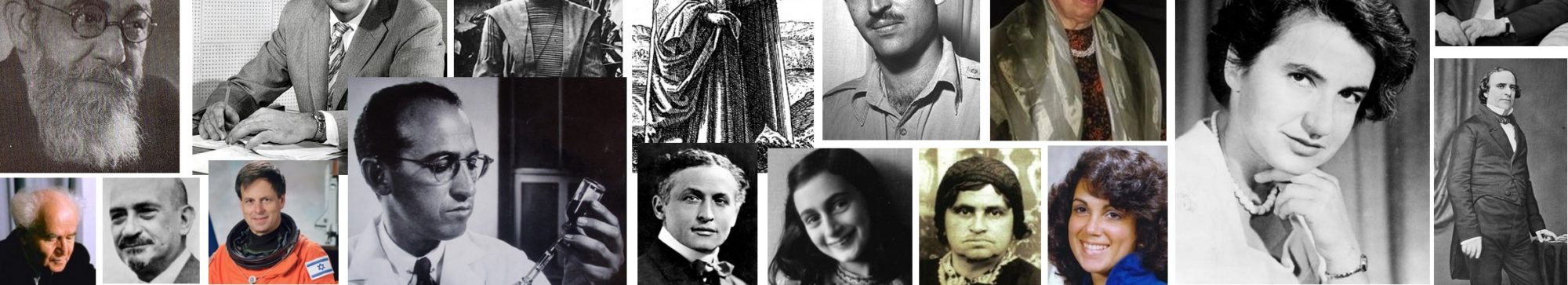

Did You Know These People are Jewish?

Words of the Week

Happiness is not a life without pain, but rather a life in which the pain is traded for a worthy price.

– Orson Scott Card