The First Zionist (and the First Modern Ba’al Teshuva)

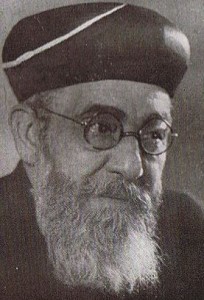

Nathan Birnbaum (1864-1937) was born in Vienna to a traditional Jewish family of Hungarian and Galician heritage. He studied law and philosophy at the University of Vienna, where he founded Kadimah, the first nationalist Jewish student association. He also started a new magazine called Selbstemanzipation! (“Self-Emancipation!) In fact, it was in an 1890 article for his magazine that Birnbaum coined the terms “Zionism” and “Zionist”. Two years later, he coined the term “political Zionism”, as distinct from the religious Zionism that has always existed in Judaism. Birnbaum’s writings were hugely popular and helped ignite the modern Zionist movement. They also played a role in inspiring Theodor Herzl. At the First Zionist Congress in 1897, Birnbaum was elected Secretary General. However, he soon had a change of heart when he saw how Zionism was becoming too secular and too political. Instead, he began to advocate for “Jewish cultural autonomy”, also called golus (or galut) nationalism. He hoped Jews would be recognized as a distinct and semi-autonomous people within the countries in which they dwelled. Birnbaum ran for Austrian parliament and while he did win the election, corruption and anti-Semitism prevented him from taking his seat. Birnbaum was a huge proponent of “Yiddishism”, and to make Jews proud of their culture and language. In 1908, he convened the first Conference for the Yiddish Language, and even traveled to America to promote the revival of Yiddish. During this trip, he had a meeting with US President Teddy Roosevelt. Birnbaum eventually realized that true salvation for the Jews can only come from adherence to Torah and Jewish law. In 1916, he became a ba’al teshuvah and began to live a strictly Orthodox life. Three years later, he became the General Secretary of Agudas Yisroel (originally an umbrella organization for Eastern European Orthodox Jews, and today also a political party in Israel). He wrote a popular text called Gottesvolk (“God’s People”), where he outlined his plan for reviving Judaism and laid out a vision of the ideal Jewish community. He argued passionately against “modern paganism” and warned about the dangers of godless secularism, quite accurately foreseeing how it could destroy society. He affirmed that settling and living in Israel was still important, of course, but for spiritual reasons, not political ones. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Birnbaum fled with his family to the Netherlands, where he lived out the last few years of his life. Today there is a street in Jerusalem named after him. He has been called a “prophetic personality” and the “first modern ba’al teshuvah”.

Nathan Birnbaum (1864-1937) was born in Vienna to a traditional Jewish family of Hungarian and Galician heritage. He studied law and philosophy at the University of Vienna, where he founded Kadimah, the first nationalist Jewish student association. He also started a new magazine called Selbstemanzipation! (“Self-Emancipation!) In fact, it was in an 1890 article for his magazine that Birnbaum coined the terms “Zionism” and “Zionist”. Two years later, he coined the term “political Zionism”, as distinct from the religious Zionism that has always existed in Judaism. Birnbaum’s writings were hugely popular and helped ignite the modern Zionist movement. They also played a role in inspiring Theodor Herzl. At the First Zionist Congress in 1897, Birnbaum was elected Secretary General. However, he soon had a change of heart when he saw how Zionism was becoming too secular and too political. Instead, he began to advocate for “Jewish cultural autonomy”, also called golus (or galut) nationalism. He hoped Jews would be recognized as a distinct and semi-autonomous people within the countries in which they dwelled. Birnbaum ran for Austrian parliament and while he did win the election, corruption and anti-Semitism prevented him from taking his seat. Birnbaum was a huge proponent of “Yiddishism”, and to make Jews proud of their culture and language. In 1908, he convened the first Conference for the Yiddish Language, and even traveled to America to promote the revival of Yiddish. During this trip, he had a meeting with US President Teddy Roosevelt. Birnbaum eventually realized that true salvation for the Jews can only come from adherence to Torah and Jewish law. In 1916, he became a ba’al teshuvah and began to live a strictly Orthodox life. Three years later, he became the General Secretary of Agudas Yisroel (originally an umbrella organization for Eastern European Orthodox Jews, and today also a political party in Israel). He wrote a popular text called Gottesvolk (“God’s People”), where he outlined his plan for reviving Judaism and laid out a vision of the ideal Jewish community. He argued passionately against “modern paganism” and warned about the dangers of godless secularism, quite accurately foreseeing how it could destroy society. He affirmed that settling and living in Israel was still important, of course, but for spiritual reasons, not political ones. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Birnbaum fled with his family to the Netherlands, where he lived out the last few years of his life. Today there is a street in Jerusalem named after him. He has been called a “prophetic personality” and the “first modern ba’al teshuvah”.

Yom Kippur Begins Tuesday Evening – Gmar Chatima Tova!

9 Yom Kippur Myths and Misconceptions

Words of the Week

When one stands in prayer, he should place his feet together side by side. He should set his eyes downwards as if he is looking at the ground, and his heart upwards as if he is standing in Heaven.

– Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (“Maimonides”, 1138-1204), Mishneh Torah