The Rebel Evolutionist

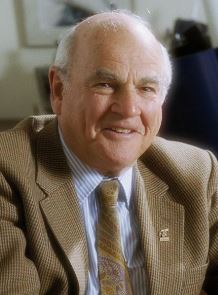

Lynn Petra Alexander (1938-2011) was born in Chicago to a prominent Jewish (and passionately-Zionist) family. She got accepted to the University of Chicago when she was just 15 years old, and graduated with a BA four years later. That same year, she married (former Jew of the Week) Carl Sagan, then on his way to becoming a world-renowned scientist himself. She then went to the University of Wisconsin and earned her Master’s in genetics and zoology, followed by a PhD from UC Berkeley. Around that time, she divorced Carl Sagan and later married another scientist, Thomas Margulis. Although she divorced him as well, she kept the last name and is best known today as Lynn Margulis. In 1966, she became a biology professor at the University of Boston and remained there until 1988, when she became Distinguished Professor of Biology and Geosciences at the University of Massachusetts. Her 1967 paper “On the Origin of Mitosing Cells” was initially rejected by fifteen journals and stirred a great deal of controversy before being confirmed experimentally in 1978. Much of her research (and the opposition to it) was based on demonstrating major flaws within Darwin’s evolutionary theory. She would say that “Natural selection eliminates and maybe maintains, but it doesn’t create.” Margulis offered one hypothesis of her own, endosymbiosis, now a widely-accepted theory in biology and a key mechanism of evolution. Margulis also co-authored the first paper on the now-famous Gaia hypothesis regarding the intricate interactions between living things and the planet. Margulis worked tirelessly to the last days of her life. She co-authored another big (and controversial) paper in 2009—at the age of 71! Margulis has been called a “scientific rebel” and won countless awards, including a National Medal of Science from President Bill Clinton and a NASA Public Service Award for Astrobiology. She also has 15 honourary doctorates and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In 2002, she was ranked among the 50 most important women in science.

Lynn Petra Alexander (1938-2011) was born in Chicago to a prominent Jewish (and passionately-Zionist) family. She got accepted to the University of Chicago when she was just 15 years old, and graduated with a BA four years later. That same year, she married (former Jew of the Week) Carl Sagan, then on his way to becoming a world-renowned scientist himself. She then went to the University of Wisconsin and earned her Master’s in genetics and zoology, followed by a PhD from UC Berkeley. Around that time, she divorced Carl Sagan and later married another scientist, Thomas Margulis. Although she divorced him as well, she kept the last name and is best known today as Lynn Margulis. In 1966, she became a biology professor at the University of Boston and remained there until 1988, when she became Distinguished Professor of Biology and Geosciences at the University of Massachusetts. Her 1967 paper “On the Origin of Mitosing Cells” was initially rejected by fifteen journals and stirred a great deal of controversy before being confirmed experimentally in 1978. Much of her research (and the opposition to it) was based on demonstrating major flaws within Darwin’s evolutionary theory. She would say that “Natural selection eliminates and maybe maintains, but it doesn’t create.” Margulis offered one hypothesis of her own, endosymbiosis, now a widely-accepted theory in biology and a key mechanism of evolution. Margulis also co-authored the first paper on the now-famous Gaia hypothesis regarding the intricate interactions between living things and the planet. Margulis worked tirelessly to the last days of her life. She co-authored another big (and controversial) paper in 2009—at the age of 71! Margulis has been called a “scientific rebel” and won countless awards, including a National Medal of Science from President Bill Clinton and a NASA Public Service Award for Astrobiology. She also has 15 honourary doctorates and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences. In 2002, she was ranked among the 50 most important women in science.

Words of the Week

We never judge a statement by its author, but only on its own merit.

– Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (1707-1746), Derekh Tevunot

Mildred Cohn (1913-2009) was born in New York to Jewish-Russian immigrants. Her father was a rabbi and Cohn grew up in a religious, Yiddish-speaking home, though one which also prioritized secular education and the arts. Cohn graduated high school by the age of 14 and got her Bachelor’s degree in biochemistry at 18, followed by her Master’s from Columbia University. Unable to afford any further schooling, Cohn got a job researching for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which would later become NASA. She was the only woman among seventy men, and was told she shouldn’t expect any promotions. Two years later, she had enough money to return to school, pursuing her PhD at Columbia under recent Nobel Prize-winner Harold Urey. Cohn focused her work on carbon and oxygen isotopes. From there, she moved on to Washington University to do research on metabolism using sulfur isotopes. Later, she switched to using nuclear magnetic resonance and made a huge breakthrough in 1958 when she was able to visualize ATP, the central energy molecule that powers human cells and essentially all living things. Cohn discovered much of what we know about ATP and how it works. All in all, she wrote 160 scientific papers and won numerous awards, including the National Medal of Science (awarded to her by President Reagan). She was the first female editor of the Journal of Biological Chemistry and the first female president of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. In 2009 she was inducted in the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Cohn was married to renowned Jewish physicist Henry Primakoff. Many of her ATP discoveries came while she was working at the lab of another great Jewish scientist, Gerty Cori.

Mildred Cohn (1913-2009) was born in New York to Jewish-Russian immigrants. Her father was a rabbi and Cohn grew up in a religious, Yiddish-speaking home, though one which also prioritized secular education and the arts. Cohn graduated high school by the age of 14 and got her Bachelor’s degree in biochemistry at 18, followed by her Master’s from Columbia University. Unable to afford any further schooling, Cohn got a job researching for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which would later become NASA. She was the only woman among seventy men, and was told she shouldn’t expect any promotions. Two years later, she had enough money to return to school, pursuing her PhD at Columbia under recent Nobel Prize-winner Harold Urey. Cohn focused her work on carbon and oxygen isotopes. From there, she moved on to Washington University to do research on metabolism using sulfur isotopes. Later, she switched to using nuclear magnetic resonance and made a huge breakthrough in 1958 when she was able to visualize ATP, the central energy molecule that powers human cells and essentially all living things. Cohn discovered much of what we know about ATP and how it works. All in all, she wrote 160 scientific papers and won numerous awards, including the National Medal of Science (awarded to her by President Reagan). She was the first female editor of the Journal of Biological Chemistry and the first female president of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. In 2009 she was inducted in the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Cohn was married to renowned Jewish physicist Henry Primakoff. Many of her ATP discoveries came while she was working at the lab of another great Jewish scientist, Gerty Cori. Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori (1896-1957) was born in Prague. Her father was a chemist who had invented a new way of refining sugar. At 16, Cori decided to become a doctor, but found that she was missing nearly all the prerequisites. So, in one year she took eighteen years-worth of courses in Latin, science, and math. Cori passed her entrance exam and was among the first women ever to be admitted to Prague’s medical school. After graduating, she worked at a children’s hospital and also did research on blood disorders, the thyroid gland, and the body’s ability to regular temperature. Due to persistent food shortages and rising anti-Semitism after World War I, Cori and her husband (also a doctor and scientist) left Prague and moved to New York. The couple did research together at what is now the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, focusing on glucose metabolism. Cori published 11 papers of her own, and another 50 together with her husband. By 1929, the Coris had figured out how the body metabolized glucose in the absence of oxygen, a process now known as the Cori Cycle. For this, they won a Nobel Prize in 1947. This made Cori the first American woman to win a Nobel Prize (and only the third woman overall), as well as the first woman ever to win a Nobel Prize in Medicine. In 1931, the couple took over a lab at Washington University (with Cori being paid one-tenth her husband’s salary). Here they made many more vital scientific discoveries, and mentored a new generation of scientists—six of which went on to win Nobel Prizes of their own. For this reason, their lab was deemed a National Historic Landmark in 2004. Like Mildred Cohn, Gerty Cori won countless awards and was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. There are craters on the Moon and on Venus named after her, as well as a commemorative US stamp. After battling the disease for a decade, Cori succumbed to bone cancer, likely caused by her extensive work with X-rays.

Gerty Theresa Radnitz Cori (1896-1957) was born in Prague. Her father was a chemist who had invented a new way of refining sugar. At 16, Cori decided to become a doctor, but found that she was missing nearly all the prerequisites. So, in one year she took eighteen years-worth of courses in Latin, science, and math. Cori passed her entrance exam and was among the first women ever to be admitted to Prague’s medical school. After graduating, she worked at a children’s hospital and also did research on blood disorders, the thyroid gland, and the body’s ability to regular temperature. Due to persistent food shortages and rising anti-Semitism after World War I, Cori and her husband (also a doctor and scientist) left Prague and moved to New York. The couple did research together at what is now the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, focusing on glucose metabolism. Cori published 11 papers of her own, and another 50 together with her husband. By 1929, the Coris had figured out how the body metabolized glucose in the absence of oxygen, a process now known as the Cori Cycle. For this, they won a Nobel Prize in 1947. This made Cori the first American woman to win a Nobel Prize (and only the third woman overall), as well as the first woman ever to win a Nobel Prize in Medicine. In 1931, the couple took over a lab at Washington University (with Cori being paid one-tenth her husband’s salary). Here they made many more vital scientific discoveries, and mentored a new generation of scientists—six of which went on to win Nobel Prizes of their own. For this reason, their lab was deemed a National Historic Landmark in 2004. Like Mildred Cohn, Gerty Cori won countless awards and was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. There are craters on the Moon and on Venus named after her, as well as a commemorative US stamp. After battling the disease for a decade, Cori succumbed to bone cancer, likely caused by her extensive work with X-rays.