Inventor of Buses

Simon Kremser (1775-1851) was born in the German city of Breslau (now Wroclaw, Poland). He followed in the footsteps of his father, a wealthy merchant. During the Napoleonic Wars, Kremser helped to provide funds for the Silesian Army against Napoleon, and managed the Prussian royal family’s war chest. He was awarded the Iron Cross, and was eventually granted citizenship, becoming one of the first Jews to be a German citizen. In 1825, Kremser had an idea for a public carriage line that would quickly and cheaply transport people across Berlin. He got permission from King Friedrich William III, and designed a large horse-drawn carriage that could seat up to 20 people. Such carriages are still known as “kremsers” in Germany today. By 1835, Kremser ran three different “bus” lines in Berlin. The idea of public buses soon spread across Europe. As the king’s official hauler, Kremser was also the one commissioned to return the famous Brandenburg Gate Quadriga to Berlin in 1814 after it had been snatched by Napoleon. Little else is known of Kremser, and no picture of him has survived. It is believed that he lived out his last years in Russia, where he served the royal family and was given the honorary military rank of major.

Words of the Week

The only wealth that I truly own is that which I have given away to good causes. Everything else – all my holdings – are simply under my control for the moment, but they can be lost in the next moment due to a bad decision, war, an accident or other cause which I cannot control. However, the good institutions that my money has built are forever; they can never be taken or lost.

– Sir Moses Montefiore

Yonah Yosipovich Leibensohn Kremenezky (1850-1934) was born in Odessa, Ukraine to a Russian-Jewish family. He studied electrical engineering and worked on designing Russia’s first railways. In 1874, Kremenezky moved to Berlin to further his studies at the city’s Technical University. He then got a job working for Siemens, and was sent across Europe to build the continent’s first street lighting systems, starting in Paris and ending up in Vienna in 1878, where he settled permanently. Two years later, Kremenezky founded his own factory that produced lamps and batteries—the first of its kind in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. By 1883, he had become very well-known as a scientist-industrialist (a European Edison), and Crown Prince Rudolf personally asked him to help “electrify” his empire. Kremenezky did just that, laying electrical cables and setting up lighting systems, as well as building the empire’s first power plant. Meanwhile, his lamp factory designed all sorts of new lights, including ornamental bulbs and what we now know as “Christmas lights”. Kremenezky lights were a huge hit, exported around the world, even to the United States. For playing a key role in rebuilding and repowering Vienna after World War I, Kremenezky was awarded with the Ehrenbürgerrecht, the city’s highest decoration for citizens (a street in Vienna was named after him, too). Meanwhile, back in 1896, Kremenezky had met

Yonah Yosipovich Leibensohn Kremenezky (1850-1934) was born in Odessa, Ukraine to a Russian-Jewish family. He studied electrical engineering and worked on designing Russia’s first railways. In 1874, Kremenezky moved to Berlin to further his studies at the city’s Technical University. He then got a job working for Siemens, and was sent across Europe to build the continent’s first street lighting systems, starting in Paris and ending up in Vienna in 1878, where he settled permanently. Two years later, Kremenezky founded his own factory that produced lamps and batteries—the first of its kind in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. By 1883, he had become very well-known as a scientist-industrialist (a European Edison), and Crown Prince Rudolf personally asked him to help “electrify” his empire. Kremenezky did just that, laying electrical cables and setting up lighting systems, as well as building the empire’s first power plant. Meanwhile, his lamp factory designed all sorts of new lights, including ornamental bulbs and what we now know as “Christmas lights”. Kremenezky lights were a huge hit, exported around the world, even to the United States. For playing a key role in rebuilding and repowering Vienna after World War I, Kremenezky was awarded with the Ehrenbürgerrecht, the city’s highest decoration for citizens (a street in Vienna was named after him, too). Meanwhile, back in 1896, Kremenezky had met  Jacob Liebmann Beer (1791-1864) was born near Berlin, then in the Kingdom of Prussia, to a wealthy, observant Jewish family. His father was the president of Berlin’s Jewish community and ran a large synagogue in his home. His mother received the prestigious Order of Louise from the Prussian queen, and because she was an observant Jew, got a small statue instead of the traditional cross. The Beer children received the best secular education, as well as private tutors in Jewish studies. All three sons became famous: Wilhelm Beer as an astronomer, Michael Beer as writer, and Jacob Beer as a composer. When his beloved grandfather Meyer passed away, Jacob added the name to his own, changing it to Meyerbeer. He also vowed never to abandon the faith of his fathers, while many of his friends “converted” to Christianity to be accepted in society and to take on jobs otherwise barred to them. Meyerbeer was taught music from a young age by some of the best instructors of the time. He performed his first public concert at just age nine. Meyerbeer’s early work involved writing religious music for his father’s synagogue, and his first big production was a ballet-opera called The Fisherman and the Milkman, followed by the musical God and Nature, and the opera Jephtha’s Vow. He wrote beautiful pieces for the piano, clarinet, and full orchestras, and vacillated between composing and playing music himself (which he preferred). Having faced many difficulties in his youth, Meyerbeer founded the Musical Union to support up-and-coming composers. In 1813, he was appointed Court Composer for the Grand Duke of Hesse. Several years later, he felt he had lots more to learn and moved to Italy. There he wrote some of his most renowned operas. By 1824, he had become world-famous, and his 1831 grand opera, Robert le diable, made him the equivalent of a modern-day superstar. The following year, he received the Legion of Honour, the highest award in France. In 1841, he was described as the “German Messiah” who would save the Paris Opera from its death, and shortly after also became director of music for the Prussian royal court. Not surprisingly, his success and wealth drew the ire of his colleagues, and Meyerbeer faced terrible criticism and anti-Semitism (especially from Richard Wagner, once his pupil). Meyerbeer remained graceful nonetheless, and never responded to the attacks on him. He continued to compose popular works until his last day, and has been credited with being “the most frequently performed opera composer” of the 19th century. He inspired the works of later greats like Dvořák, Liszt, and Tchaikovsky. He was also a generous philanthropist, a devoted husband and father to five children, and never broke his vow to die an observant Jew. Meyerbeer remains one of the greatest musicians of all time.

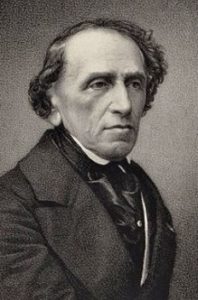

Jacob Liebmann Beer (1791-1864) was born near Berlin, then in the Kingdom of Prussia, to a wealthy, observant Jewish family. His father was the president of Berlin’s Jewish community and ran a large synagogue in his home. His mother received the prestigious Order of Louise from the Prussian queen, and because she was an observant Jew, got a small statue instead of the traditional cross. The Beer children received the best secular education, as well as private tutors in Jewish studies. All three sons became famous: Wilhelm Beer as an astronomer, Michael Beer as writer, and Jacob Beer as a composer. When his beloved grandfather Meyer passed away, Jacob added the name to his own, changing it to Meyerbeer. He also vowed never to abandon the faith of his fathers, while many of his friends “converted” to Christianity to be accepted in society and to take on jobs otherwise barred to them. Meyerbeer was taught music from a young age by some of the best instructors of the time. He performed his first public concert at just age nine. Meyerbeer’s early work involved writing religious music for his father’s synagogue, and his first big production was a ballet-opera called The Fisherman and the Milkman, followed by the musical God and Nature, and the opera Jephtha’s Vow. He wrote beautiful pieces for the piano, clarinet, and full orchestras, and vacillated between composing and playing music himself (which he preferred). Having faced many difficulties in his youth, Meyerbeer founded the Musical Union to support up-and-coming composers. In 1813, he was appointed Court Composer for the Grand Duke of Hesse. Several years later, he felt he had lots more to learn and moved to Italy. There he wrote some of his most renowned operas. By 1824, he had become world-famous, and his 1831 grand opera, Robert le diable, made him the equivalent of a modern-day superstar. The following year, he received the Legion of Honour, the highest award in France. In 1841, he was described as the “German Messiah” who would save the Paris Opera from its death, and shortly after also became director of music for the Prussian royal court. Not surprisingly, his success and wealth drew the ire of his colleagues, and Meyerbeer faced terrible criticism and anti-Semitism (especially from Richard Wagner, once his pupil). Meyerbeer remained graceful nonetheless, and never responded to the attacks on him. He continued to compose popular works until his last day, and has been credited with being “the most frequently performed opera composer” of the 19th century. He inspired the works of later greats like Dvořák, Liszt, and Tchaikovsky. He was also a generous philanthropist, a devoted husband and father to five children, and never broke his vow to die an observant Jew. Meyerbeer remains one of the greatest musicians of all time.