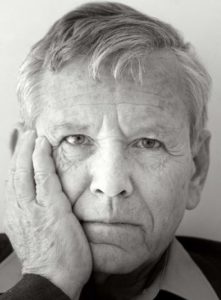

Israel’s Greatest Writer

Amos Oz (Credit: Michiel Hendryckx)

Amos Klausner (1939-2018) was born in Jerusalem, the only child of Lithuanian- and Polish-Jewish parents. Although his family was entirely secular, Amos was sent to a religious school because the only other option was a socialist school that his parents vehemently opposed. At 14, he decided to go off on his own, changed his last name to “Oz”, and joined a kibbutz. He wasn’t fit for kibbutz work, and was made fun of constantly. Oz found solace in writing, and was eventually given permission by the kibbutz to have one day off a week to do so. After three years of military service, the kibbutz sent him to study literature and philosophy at the Hebrew University. He graduated in 1963, returning to the kibbutz to work as a teacher, and continuing to write once a week. Two years later, he published his first book, a collection of short stories. It was his third publication, the novel My Michael, that became a bestseller and thrust him into fame. (Even after this, his kibbutz only allowed three days a week to write!) Oz would follow that up with 13 more popular novels, four more collections of prized short stories, and another twelve of essays on various topics, along with two children’s books. The most famous of these is his 2002 memoir, A Tale of Love and Darkness, which was adapted into a film by Natalie Portman. All in all, he produced some 40 books and 450 essays, with his work translated into nearly 50 languages – more than any other Israeli writer. Oz served in both the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War. In 1987, he came a professor of Hebrew literature at Ben-Gurion University, a post he held until 2014. While often seen as the face of the Israeli left, Oz defended Israel in its military campaigns, explaining their necessity and never failing to point out the evils of the terrorist enemy. He was one of the first to speak of a two-state solution (penning an essay immediately after the Six-Day War) and was opposed to Israeli settlements, but supported the West Bank barrier wall. He admitted that Israelis have always been willing to work for peace while Arabs not so much, and said that it takes “two hands to clap”. He remained a staunch Zionist his entire life and vocally opposed non-Zionists. In these ways, he mitigated the Israeli left, trying to keep them from falling into extremes, and from getting into the habit of blaming Israel for everything. Oz worked tirelessly for peace, and some of his actions in doing so were severely criticized (like the recent letter he sent to imprisoned Palestinian activist/terrorist Marwan Barghouti). Among his long list of awards is the Israel Prize, the French Legion of Honour, the Spanish Order of Civil Merit, and the South Korean Park Kyong-ni Prize for Literature. Sadly, Oz passed away last week. The man who has been called Israel’s greatest writer was laid to rest in the kibbutz that was his home for over three decades.

Words of the Week

The story of modern Israel, as many have noted, is a miracle unlike any… It is a robust and inclusive democracy, and is at the leading edge of science and technology… What hypocrites demand of Israelis and the scrutiny Israel is subjected to by them, they would not dare make of any other nation.

– Salim Mansur

Simone Annie Liline Jacob (1927-2017) was born and raised in Nice, France. Just after finishing high school, her entire family was rounded up and sent to Auschwitz. Jacob’s mother, father, and brother perished in the Holocaust; two sisters survived. After being liberated from the camps, Jacob settled in Paris and studied law and politics. There, she met her soon-to-be husband Antoine Veil, with whom she would be married for 66 years. In 1956, she became a magistrate, and worked for the French Ministry of Justice, heading its penitentiary system. She was hailed for her role in dramatically improving prison conditions, and was known to regularly visit prisons on her days off. By 1964, Veil had become France’s Director of Civil Affairs. She worked tirelessly for women’s rights, and succeeded in finally getting French women full equality in legal matters. In 1970, Veil took over as secretary general of the Supreme Magistracy, then became Minister of Health in 1974, making her the first female minister in French history. Among her most famous laws was opening access to contraceptives, legalizing abortion (still known as “Veil’s Law”, which she intended only as a “last resort, for desperate situations”), and banning smoking in public areas. She also introduced maternity benefits, improved hospital conditions, enhanced the medical school curriculum, and worked to stop the illegal harvesting of organs from the deceased. Meanwhile, Veil worked for the European Economic Community, believing that a unified Europe was the only way to prevent another devastating war. When the EEC was reformed as the European Union, she was elected to its parliament, and shortly after, as its first president. She would serve on the European Parliament until 1993, in its Environment, Health, and Political Affairs Committees. Veil then returned to the French government, serving as Minister of State and Minister of Health until 1995. She continued her work in France and Europe until her last days, and faced a great deal of anti-Semitism throughout, including death threats and swastikas painted on her car and home. Not surprisingly, in recent years her greatest passion was Holocaust education, and she was president of the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah. Among her many awards are the prestigious Charlemagne Prize, the Truman Award for Peace, the Legion of Honour, and the Order of the British Empire. In 2008, Veil became one of the forty “immortal” members of the illustrious French Academy. She also held 18 honourary degrees, including one from Yale and another from Yeshiva University. Sadly, Simone Veil passed away earlier this year, just shy of her 90th birthday. She was laid to rest with full military honours in the Pantheon, Paris’ famous mausoleum, alongside just 71 of France’s most cherished figures, including Voltaire and Rousseau. She remains among the most revered women in French history.

Simone Annie Liline Jacob (1927-2017) was born and raised in Nice, France. Just after finishing high school, her entire family was rounded up and sent to Auschwitz. Jacob’s mother, father, and brother perished in the Holocaust; two sisters survived. After being liberated from the camps, Jacob settled in Paris and studied law and politics. There, she met her soon-to-be husband Antoine Veil, with whom she would be married for 66 years. In 1956, she became a magistrate, and worked for the French Ministry of Justice, heading its penitentiary system. She was hailed for her role in dramatically improving prison conditions, and was known to regularly visit prisons on her days off. By 1964, Veil had become France’s Director of Civil Affairs. She worked tirelessly for women’s rights, and succeeded in finally getting French women full equality in legal matters. In 1970, Veil took over as secretary general of the Supreme Magistracy, then became Minister of Health in 1974, making her the first female minister in French history. Among her most famous laws was opening access to contraceptives, legalizing abortion (still known as “Veil’s Law”, which she intended only as a “last resort, for desperate situations”), and banning smoking in public areas. She also introduced maternity benefits, improved hospital conditions, enhanced the medical school curriculum, and worked to stop the illegal harvesting of organs from the deceased. Meanwhile, Veil worked for the European Economic Community, believing that a unified Europe was the only way to prevent another devastating war. When the EEC was reformed as the European Union, she was elected to its parliament, and shortly after, as its first president. She would serve on the European Parliament until 1993, in its Environment, Health, and Political Affairs Committees. Veil then returned to the French government, serving as Minister of State and Minister of Health until 1995. She continued her work in France and Europe until her last days, and faced a great deal of anti-Semitism throughout, including death threats and swastikas painted on her car and home. Not surprisingly, in recent years her greatest passion was Holocaust education, and she was president of the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah. Among her many awards are the prestigious Charlemagne Prize, the Truman Award for Peace, the Legion of Honour, and the Order of the British Empire. In 2008, Veil became one of the forty “immortal” members of the illustrious French Academy. She also held 18 honourary degrees, including one from Yale and another from Yeshiva University. Sadly, Simone Veil passed away earlier this year, just shy of her 90th birthday. She was laid to rest with full military honours in the Pantheon, Paris’ famous mausoleum, alongside just 71 of France’s most cherished figures, including Voltaire and Rousseau. She remains among the most revered women in French history.