The Man Behind Modern Hebrew

Eliezer Yitzhak ben Yehuda Leib Perlman (1858-1922) was born in what is now Belarus to a religious, Yiddish-speaking, Chabad family. Before his bar mitzvah he was already recognized as a genius in Torah and Talmud. While studying to become a rabbi, Ben-Yehuda was first exposed to some of the Hebrew works of the medieval Sephardic rabbis (such as Ibn Ezra) who wrote poems, stories, and even textbooks of Hebrew grammar. Meanwhile, he came across contemporary, secular (Haskalah) literature written in Hebrew, most notably a Hebrew-only Zionist newspaper called HaShahar. This sparked a passion for languages in general, and Hebrew in particular. Ben-Yehuda plunged into the study of the grammar, history, and development of Hebrew, and also started learning Russian, German, and French. He soon realized the tremendous power of language, and that the only thing truly uniting all Jews around the world—whether Ashkenazi or Sephardi, religious or secular—was Hebrew. In 1877, Ben-Yehuda moved to Paris to study medicine and Middle Eastern history at the famous Sorbonne University. While sitting at a café one day, he met a fellow Jew who started speaking to him in Hebrew. This was the moment that convinced Ben-Yehuda that it was possible to turn Hebrew into a common, spoken language. While some Zionists (like Herzl himself) initially sought to make Yiddish or even German the official language of what would be the Jewish State, Ben-Yehuda knew that it had to be Hebrew. Upon graduating in 1881, he made aliyah and settled in Jerusalem. Ben-Yehuda taught at the Torah and Avoda School, where he devised his immersive ivrit b’ivrit system of learning. He spent the rest of his time writing and developing the language. He founded the Hebrew Language Committee (still operating today) to dig up ancient Hebrew words and to coin new words for modern phenomena, based primarily on ancient Biblical, Aramaic (often Talmudic) terms, as well as from Arabic roots. Ben-Yehuda coined words like glida (“ice cream”), ofanaim (“bicycle”), magevet (“towel”), and rakevet (“train”) using Biblical roots for similar terms. Meanwhile, he wrote for the Havatzelet newspaper, edited the Hashkafa newspaper, then launched his own periodical, HaTzvi, where he would introduce his new words (such as iton, “newspaper”!) He published the first dictionary of Modern Hebrew, a whopping 11-volume tome (later expanded to 17 volumes). Ben-Yehuda raised his children strictly in Hebrew. His son, Ben-Zion, is considered the first native speaker of Modern Hebrew. Some people inaccurately state that Hebrew was a “dead” or “extinct” language before Ben-Yehuda and the Zionists. This is, of course, completely inaccurate since Hebrew has always been used by Jews throughout the centuries, particularly in prayer and for the writing and teaching of holy texts. What Ben-Yehuda did was systematize Hebrew, adapt it to modern times, and transform it into a commonly-spoken tongue, as historian Cecil Roth summed it up: “Before Ben-Yehuda, Jews could speak Hebrew; after him, they did.”

Eliezer Yitzhak ben Yehuda Leib Perlman (1858-1922) was born in what is now Belarus to a religious, Yiddish-speaking, Chabad family. Before his bar mitzvah he was already recognized as a genius in Torah and Talmud. While studying to become a rabbi, Ben-Yehuda was first exposed to some of the Hebrew works of the medieval Sephardic rabbis (such as Ibn Ezra) who wrote poems, stories, and even textbooks of Hebrew grammar. Meanwhile, he came across contemporary, secular (Haskalah) literature written in Hebrew, most notably a Hebrew-only Zionist newspaper called HaShahar. This sparked a passion for languages in general, and Hebrew in particular. Ben-Yehuda plunged into the study of the grammar, history, and development of Hebrew, and also started learning Russian, German, and French. He soon realized the tremendous power of language, and that the only thing truly uniting all Jews around the world—whether Ashkenazi or Sephardi, religious or secular—was Hebrew. In 1877, Ben-Yehuda moved to Paris to study medicine and Middle Eastern history at the famous Sorbonne University. While sitting at a café one day, he met a fellow Jew who started speaking to him in Hebrew. This was the moment that convinced Ben-Yehuda that it was possible to turn Hebrew into a common, spoken language. While some Zionists (like Herzl himself) initially sought to make Yiddish or even German the official language of what would be the Jewish State, Ben-Yehuda knew that it had to be Hebrew. Upon graduating in 1881, he made aliyah and settled in Jerusalem. Ben-Yehuda taught at the Torah and Avoda School, where he devised his immersive ivrit b’ivrit system of learning. He spent the rest of his time writing and developing the language. He founded the Hebrew Language Committee (still operating today) to dig up ancient Hebrew words and to coin new words for modern phenomena, based primarily on ancient Biblical, Aramaic (often Talmudic) terms, as well as from Arabic roots. Ben-Yehuda coined words like glida (“ice cream”), ofanaim (“bicycle”), magevet (“towel”), and rakevet (“train”) using Biblical roots for similar terms. Meanwhile, he wrote for the Havatzelet newspaper, edited the Hashkafa newspaper, then launched his own periodical, HaTzvi, where he would introduce his new words (such as iton, “newspaper”!) He published the first dictionary of Modern Hebrew, a whopping 11-volume tome (later expanded to 17 volumes). Ben-Yehuda raised his children strictly in Hebrew. His son, Ben-Zion, is considered the first native speaker of Modern Hebrew. Some people inaccurately state that Hebrew was a “dead” or “extinct” language before Ben-Yehuda and the Zionists. This is, of course, completely inaccurate since Hebrew has always been used by Jews throughout the centuries, particularly in prayer and for the writing and teaching of holy texts. What Ben-Yehuda did was systematize Hebrew, adapt it to modern times, and transform it into a commonly-spoken tongue, as historian Cecil Roth summed it up: “Before Ben-Yehuda, Jews could speak Hebrew; after him, they did.”

The Kabbalah of Yom Ha‘Atzmaut

Words of the Week

For everything there is needed only one wise, clever and active man, with the initiative to devote all his energies to it, and the matter will progress, all obstacles in the way notwithstanding… In every new event, every step, even the smallest in the path of progress, it is necessary that there be one pioneer who will lead the way without leaving any possibility of turning back.

– Eliezer Ben-Yehuda

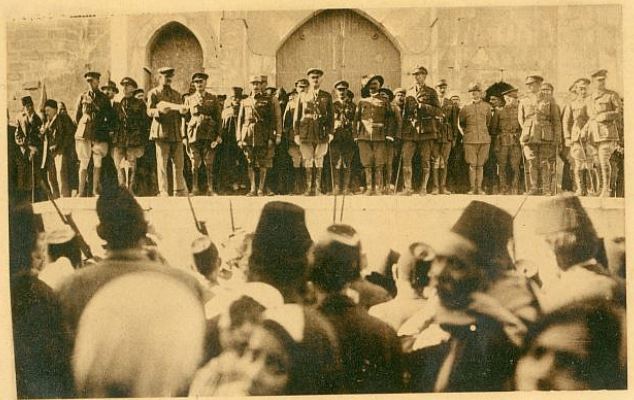

Abraham Tzvi Idelsohn (1882-1938) was born in Latvia to a religious Jewish family. He studied to be a synagogue cantor. At 27, he made aliyah to Israel and worked as a musician and composer. In 1919, he opened a Jewish music school. A few years later, he left for Ohio where he served as professor of Jewish music at Hebrew Union College, the major seminary of Reform Judaism. Between 1914 and 1932 he published his ten-volume magnum opus, Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Melodies. Many consider him “the father of Jewish musicology”. His most famous melody is undoubtedly ‘Hava Nagila’. In December of 1917, British army general Edmund Allenby defeated the Ottomans and conquered the Holy Land for Great Britain. The Jews of Israel were elated, and celebrated the general’s arrival in Jerusalem. They asked Idelsohn to compose a song for the special occasion. Idelsohn remembered an old happy tune he had adapted from a Hasidic niggun. The song was a hit. A few years later, he asked his music class to write words for the song.

Abraham Tzvi Idelsohn (1882-1938) was born in Latvia to a religious Jewish family. He studied to be a synagogue cantor. At 27, he made aliyah to Israel and worked as a musician and composer. In 1919, he opened a Jewish music school. A few years later, he left for Ohio where he served as professor of Jewish music at Hebrew Union College, the major seminary of Reform Judaism. Between 1914 and 1932 he published his ten-volume magnum opus, Thesaurus of Hebrew Oriental Melodies. Many consider him “the father of Jewish musicology”. His most famous melody is undoubtedly ‘Hava Nagila’. In December of 1917, British army general Edmund Allenby defeated the Ottomans and conquered the Holy Land for Great Britain. The Jews of Israel were elated, and celebrated the general’s arrival in Jerusalem. They asked Idelsohn to compose a song for the special occasion. Idelsohn remembered an old happy tune he had adapted from a Hasidic niggun. The song was a hit. A few years later, he asked his music class to write words for the song. A young Moshe Nathanson (1899-1981) was in that class, and wrote a couple of simple lines based on Scriptural verses from Psalm 118. The rest is history. Nathanson was born in Jerusalem, the son of a rabbi. In 1922 he moved to Canada and double-majored in law and music at McGill University. He ended up studying at what is now the prestigious Julliard School of Music in New York. From there, he was hired to be the cantor of the first Reconstructionist Synagogue, and served in that role for the next 48 years. He wrote an important four-volume tome of liturgical songs. Nathanson also spent 10 years broadcasting Jewish music on American airwaves (“Voice of Jerusalem”) and dedicated much of his life to promoting Jewish folk music. Today, Nathanson’s and Idelsohn’s ‘Hava Nagila’ is the most recognizable Jewish/Hebrew song in the world, and a staple of every bar mitzvah and wedding. There is even a full-length documentary about it, called Hava Nagila (The Movie). This past year marked the song’s centennial anniversary.

A young Moshe Nathanson (1899-1981) was in that class, and wrote a couple of simple lines based on Scriptural verses from Psalm 118. The rest is history. Nathanson was born in Jerusalem, the son of a rabbi. In 1922 he moved to Canada and double-majored in law and music at McGill University. He ended up studying at what is now the prestigious Julliard School of Music in New York. From there, he was hired to be the cantor of the first Reconstructionist Synagogue, and served in that role for the next 48 years. He wrote an important four-volume tome of liturgical songs. Nathanson also spent 10 years broadcasting Jewish music on American airwaves (“Voice of Jerusalem”) and dedicated much of his life to promoting Jewish folk music. Today, Nathanson’s and Idelsohn’s ‘Hava Nagila’ is the most recognizable Jewish/Hebrew song in the world, and a staple of every bar mitzvah and wedding. There is even a full-length documentary about it, called Hava Nagila (The Movie). This past year marked the song’s centennial anniversary.