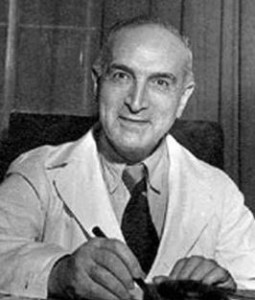

Selman Abraham Waksman (1888-1973) was born near Kiev to Jewish-Russian parents. At 22, he immigrated to the U.S. and began his studies at Rutgers University, where he got a Masters in Science before getting his Ph.D. in biology at UC Berkeley. He then headed back to Rutgers to take over the soil microbiology lab, focusing on the study of soil organisms and decomposition. Building on the work of previous scientists, Waksman soon found that bacterial substances could be used to fight bacterial infections. He shifted his lab’s focus towards finding “antibiotics” – a term which he coined. Over the next couple of decades, his lab discovered a dozen antibiotic compounds.

Albert Schatz

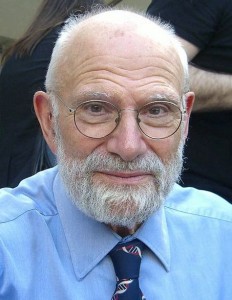

Most important of these was streptomycin, discovered by Waksman’s student Albert Israel Schatz (1920-2005). Schatz also came from Jewish-Russian lineage and originally wanted to be a farmer. He studied soil microbiology, and after serving in a military hospital during World War II, decided to research treatments for tuberculosis. Working in Waksman’s lab, Schatz discovered and named “streptomycin”, which would become one of the most important antibiotics in history, and is still found on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines. Schatz made no profit from his discovery, giving up his rights to the drug so that it could be distributed as widely and cheaply to as many people as possible. Unfortunately, he was never given the credit he deserved, with the Nobel prize going only to Waksman in 1952. Both biologists continued their contributions to science, and were decorated with many awards. Waksman also developed microbe-resistant paint for ships, enzyme-enhanced detergents, and a compound to prevent fungal infections of vineyards. He wrote over 400 papers and published 28 books. Meanwhile, Schatz campaigned against the fluoridation of water, proposed new theories for tooth decay and the extinction of dinosaurs, and published over 700 papers and 3 textbooks. Both were ultimately credited for streptomycin, which The New York Times ranked among the Top 10 discoveries of the 20th century.

Words of the Week

“Let there be light” means that all the world – even darkness – should become a source of light and wisdom. It is our job to reveal the hidden light – especially the light that you yourself hold.

– Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe