Hepatitis B and The First Cancer Vaccine

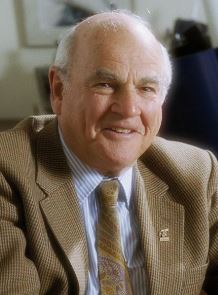

Baruch Samuel “Barry” Blumberg

Baruch Samuel Blumberg (1925-2011) was born to an Orthodox Jewish family in Brooklyn. He studied at the Yeshiva of Flatbush, and then at Far Rockaway High School in Queens (which was also attended by fellow prominent scientist and former Jew of the Week Richard Feynman). After serving in the US Navy during World War II (attaining the rank of commanding officer), Blumberg studied math and medicine at Columbia University. He earned his MD in 1951, worked as a doctor for several years, then enrolled at Oxford University to do a PhD in biochemistry. Decades later, he would be elected Master of Oxford’s prestigious Balliol College (founded all the way back in 1263), making him the first American and the first scientist to hold the title. In the 1960s, Blumberg discovered the hepatitis B antigen, and soon showed how the virus could cause liver cancer. His team began working on a diagnostic test and a vaccine, and successfully produced both. Although Blumberg had a patent on the vaccine, he gave it away freely to save as many lives as possible. (One thirty-year follow up study showed that the vaccine reduced infection from 20% to 2% of the population, and liver cancer deaths by as much as 90%. Some have therefore called it the first cancer vaccine.) Blumberg was awarded the 1976 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work with hepatitis B, and his “discoveries concerning new mechanisms for the origin and dissemination of infectious diseases.” In 1992, he co-founded the Hepatitis B Foundation, dedicated to helping people living with the disease, and funding research for a cure. Meanwhile, Blumberg taught medicine and anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. Incredibly, he also directed NASA’s Astrobiology Institute, was president of the American Philosophical Society, and a distinguished scholar advising the Scientific and Medical Advisory Board, as well as the Library of Congress. He had worked for the National Institutes of Health, and The Institute for Cancer Research. Blumberg remained Torah-observant throughout his life, and rarely missed his weekly Talmud class. He credited his Jewish studies as a youth for sharpening his mind and allowing him to excel in academia, and once said that he was drawn to medicine because of the ancient Talmudic statement that “if you save a single life, you save the whole world.” Fittingly, it has been said that Blumberg “prevented more cancer deaths than any person who’s ever lived.”

Words of the Week

Science gets the age of rocks, and religion the rock of ages; science studies how the heavens go, religion how we go to heaven.

– Renowned evolutionary bologist Stephen J. Gould

Edith Stern (b. 1952) was born in Brooklyn to impoverished Holocaust survivors who had married in the Warsaw Ghetto. Her father, Aaron Stern, had been a professor of languages (he was fluent in seven). When his daughter was born, he called a press conference – to which two reporters showed up – and declared: “I shall make her into the perfect human being.” Thus began what journalists at the time called “the Edith Project”. Stern immediately immersed his daughter in learning. He exposed her only to classical music, talked to her all the time, and taught her with flash cards. Suffering from jaw cancer and unable to work, Stern spent all of his time with Edith. By the age of 5, Edith had read through the entire Encyclopedia Britannica. Although her father did not believe in IQ tests, she nonetheless scored a 205 that same year. Edith enrolled in college at 12, earned her BS in mathematics by 15, and her Master’s at 18. By this point, she was already teaching at Michigan State University. She went on to defend her Ph.D and joined IBM’s R&D division. Today, Stern holds over 100 patents for technological innovations used in telephones, digital media, video conferencing, self-driving cars, and the internet. Stern is still a “distinguished engineer” at IBM, where she is a VP, and recently won the Kate Gleason Award for lifetime achievement in technology. Although her mother once disagreed with her father about his methods, she later concluded that it had made her a “very mature, compassionate, kind, intelligent and wise young woman.” Her father maintained that being a genius has little to do with genetics, and everything to do with how a child is raised and educated. He wrote in his 1971 The Making of a Genius: “I can foster the same meteoric IQ in the children of the Tasaday tribe, a Stone Age people living in the Philippines.”

Edith Stern (b. 1952) was born in Brooklyn to impoverished Holocaust survivors who had married in the Warsaw Ghetto. Her father, Aaron Stern, had been a professor of languages (he was fluent in seven). When his daughter was born, he called a press conference – to which two reporters showed up – and declared: “I shall make her into the perfect human being.” Thus began what journalists at the time called “the Edith Project”. Stern immediately immersed his daughter in learning. He exposed her only to classical music, talked to her all the time, and taught her with flash cards. Suffering from jaw cancer and unable to work, Stern spent all of his time with Edith. By the age of 5, Edith had read through the entire Encyclopedia Britannica. Although her father did not believe in IQ tests, she nonetheless scored a 205 that same year. Edith enrolled in college at 12, earned her BS in mathematics by 15, and her Master’s at 18. By this point, she was already teaching at Michigan State University. She went on to defend her Ph.D and joined IBM’s R&D division. Today, Stern holds over 100 patents for technological innovations used in telephones, digital media, video conferencing, self-driving cars, and the internet. Stern is still a “distinguished engineer” at IBM, where she is a VP, and recently won the Kate Gleason Award for lifetime achievement in technology. Although her mother once disagreed with her father about his methods, she later concluded that it had made her a “very mature, compassionate, kind, intelligent and wise young woman.” Her father maintained that being a genius has little to do with genetics, and everything to do with how a child is raised and educated. He wrote in his 1971 The Making of a Genius: “I can foster the same meteoric IQ in the children of the Tasaday tribe, a Stone Age people living in the Philippines.”