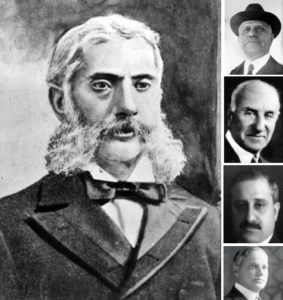

Meyer Guggenheim, with (top to bottom) Daniel, Solomon, Simon, and Benjamin

Meyer Guggenheim (1828-1905) was born in Switzerland to a traditional Ashkenazi Jewish family. At 19, he set out on his own and journeyed to the United States. After working in various shops in Philadelphia, Guggenheim opened up his own company, importing Swiss embroidery. Business went well, and he soon searched for new opportunities. In 1881, Guggenheim invested $5000 in two Colorado silver mines, and quickly realized their incredible potential. He sold all his other ventures and put all of his money into mining and smelting. With the help of his seven sons, Guggenheim quickly expanded across the US. By 1901, the family controlled the largest metal-processing plants in the US, and also owned mines in Mexico, Bolivia, Chile, and the Congo. In 1922, various disputes led to the Guggenheims being kicked out of their largest company by its own board. Soon, they sold off all of their mines. The family would invest elsewhere, and the fortune vacillated over the decades. In 1999, it ceased to be a strictly family affair with the opening of Guggenheim Partners. Today, the firm has 2300 employees, and controls $260 billion in assets worldwide (including the Los Angeles Dodgers baseball team, purchased for a record $2.15 billion in cash).

After the elder Guggenheim’s passing, his son Daniel Guggenheim (1856-1930) took over the business. By 1918, he raised the family fortune to as much as $300 million, making them among the wealthiest people in the world, as well as among the most generous philanthropists. Daniel’s son was a World War I pilot, inspiring Daniel to invest considerably in aviation technology. To this day, the most prestigious prize in aeronautics is the Daniel Guggenheim Medal. Another son, Solomon Guggenheim (1861-1949), was a patron of the arts and an avid collector. He established New York’s world-famous Guggenheim Museum. Meanwhile, Simon Guggenheim (1867-1941) served as a US senator. He established a fund in honour of his deceased son that has granted over 15,000 scholarships to date, totalling over $250 million! His $80,000 donation (equivalent to $2.5 million today) to a Colorado school was, at the time, the largest private grant ever made to a state institution. Benjamin Guggenheim (1865-1912) worked for the family business out of Paris, and in 1912 boarded the Titanic to head back home. When the iceberg hit, he was offered a place among the first women being evacuated, but rejected, saying “No woman shall remain unsaved because I was a coward.” One survivor reported that “after having helped the rescue of women and children, [he] got dressed, a rose at his buttonhole, to die.” His body was never recovered.

Words of the Week

We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when men are afraid of the light.

– Plato

Rosalie Silberman Abella (b. 1946) was born to Jewish-Polish Holocaust survivors in a displaced persons camp in Germany. When she was a child, the family moved to Halifax, and then settled in Toronto. Abella followed in her father’s footsteps and became a lawyer, graduating from the University of Toronto. She was a civil and family lawyer for five years before being appointed to the Ontario Family Court, aged just 29. This made her the youngest judge in Canada’s history – and the first pregnant one! Sixteen years later, she moved up to the Ontario Court of Appeal. Abella also sat on Ontario’s Human Rights Commission, and became a renowned expert on human rights law. Abella coined the term “employment equity” while overseeing the Royal Commission on Equality in Employment in 1983. She pioneered a number of strategies to improve employment for women, minorities, and aboriginals, which have been implemented in countries around the world. In 2004, she was appointed to Canada’s Supreme Court, making her the first Jewish woman to sit on the nation’s highest judiciary. Recently, Abella was named the Global Jurist of the Year for her work with human rights and international criminal law. Among her many other awards, she has received 37 honourary degrees, including one from Yale University – the first Canadian woman to do so. One politician said of her: “I’ve never met any judge in my life, and I know a lot of them – I used to be a lawyer – who understands people better than Rosie, and the importance of people in the judicial process. I think the human quality she brings to the bench is unsurpassed in my experience.”

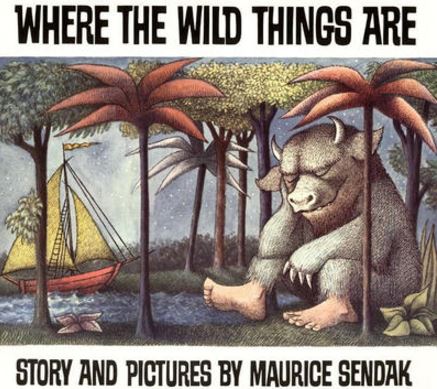

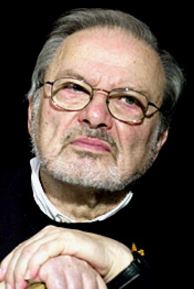

Rosalie Silberman Abella (b. 1946) was born to Jewish-Polish Holocaust survivors in a displaced persons camp in Germany. When she was a child, the family moved to Halifax, and then settled in Toronto. Abella followed in her father’s footsteps and became a lawyer, graduating from the University of Toronto. She was a civil and family lawyer for five years before being appointed to the Ontario Family Court, aged just 29. This made her the youngest judge in Canada’s history – and the first pregnant one! Sixteen years later, she moved up to the Ontario Court of Appeal. Abella also sat on Ontario’s Human Rights Commission, and became a renowned expert on human rights law. Abella coined the term “employment equity” while overseeing the Royal Commission on Equality in Employment in 1983. She pioneered a number of strategies to improve employment for women, minorities, and aboriginals, which have been implemented in countries around the world. In 2004, she was appointed to Canada’s Supreme Court, making her the first Jewish woman to sit on the nation’s highest judiciary. Recently, Abella was named the Global Jurist of the Year for her work with human rights and international criminal law. Among her many other awards, she has received 37 honourary degrees, including one from Yale University – the first Canadian woman to do so. One politician said of her: “I’ve never met any judge in my life, and I know a lot of them – I used to be a lawyer – who understands people better than Rosie, and the importance of people in the judicial process. I think the human quality she brings to the bench is unsurpassed in my experience.” Maurice Bernard Sendak (1928-2012) was born in Brooklyn to Polish-Jewish immigrants. He fell in love with books during a lengthy childhood illness, and after watching Disney’s Fantasia at age 12, decided to become an illustrator. Skipping college, Sendak first did illustrations for toy store windows before having his art published in a textbook. He then devoted himself to illustrating children’s books, including many Jewish themed ones like Good Shabbos Everybody. (Sendak once noted that one of his greatest inspirations was his father’s telling of stories from the Torah.) By the late 1950’s, he started writing his own children’s books. His most famous work came in 1963, and made Sendak a household name. Where the Wild Things Are was very controversial when first published, criticized for its edgy theme and “dark” illustrations. Sendak attributed this to his own difficult childhood, having lost many family members in the Holocaust. Nonetheless, the book became hugely popular, and went on to sell over 20 million copies worldwide. It has since been adapted into a Hollywood film and even an opera, and has been ranked as the best picture book of all time. All in all, Sendak authored 22 books, illustrated 90 more, and wrote, directed, or produced seven films. He saw himself not as a children’s author, but an “author who told the truth about children”. Sendak won many awards, including the National Medal of the Arts, and the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Award for “lasting contribution to children’s literature”. Sendak donated $1 million to New York’s Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, and left his precious collection of over 10,000 artworks, books, and manuscripts to be turned into a museum and library. He was a humble man, and avoided book signings because he “couldn’t stand the thought of parents dragging children to wait in line for hours to see a little old man in thick glasses.” After his passing of a stroke at age 83, The New York Times hailed him as “the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century.”

Maurice Bernard Sendak (1928-2012) was born in Brooklyn to Polish-Jewish immigrants. He fell in love with books during a lengthy childhood illness, and after watching Disney’s Fantasia at age 12, decided to become an illustrator. Skipping college, Sendak first did illustrations for toy store windows before having his art published in a textbook. He then devoted himself to illustrating children’s books, including many Jewish themed ones like Good Shabbos Everybody. (Sendak once noted that one of his greatest inspirations was his father’s telling of stories from the Torah.) By the late 1950’s, he started writing his own children’s books. His most famous work came in 1963, and made Sendak a household name. Where the Wild Things Are was very controversial when first published, criticized for its edgy theme and “dark” illustrations. Sendak attributed this to his own difficult childhood, having lost many family members in the Holocaust. Nonetheless, the book became hugely popular, and went on to sell over 20 million copies worldwide. It has since been adapted into a Hollywood film and even an opera, and has been ranked as the best picture book of all time. All in all, Sendak authored 22 books, illustrated 90 more, and wrote, directed, or produced seven films. He saw himself not as a children’s author, but an “author who told the truth about children”. Sendak won many awards, including the National Medal of the Arts, and the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Award for “lasting contribution to children’s literature”. Sendak donated $1 million to New York’s Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, and left his precious collection of over 10,000 artworks, books, and manuscripts to be turned into a museum and library. He was a humble man, and avoided book signings because he “couldn’t stand the thought of parents dragging children to wait in line for hours to see a little old man in thick glasses.” After his passing of a stroke at age 83, The New York Times hailed him as “the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century.”