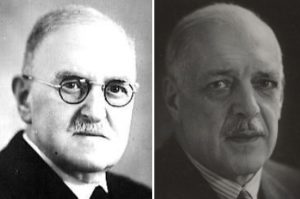

Gerald and Anton Philips

Gerald Leonard Frederik Philips (1858-1942) was born in the Netherlands, the son of a wealthy Dutch-Jewish financier (who was the first cousin of Karl Marx). In 1891, inspired by the recent invention of the light bulb, he decided to open his own light bulb and electronics company. His father purchased an abandoned factory where they set up shop and started producing carbon-filament lamps under the Philips brand the following year. The company did poorly, and nearly went bankrupt before younger brother Anton Frederik Philips (1874-1951) joined the business. A great salesman, with terrific innovations of his own, Anton quickly changed the company’s fortunes. Philips got another boost during World War I, when it filled the void left by the embargo on German electronics. By the 1920s, Philips had become a large corporation, and would soon establish the model for future electronics multinationals. After making their own vacuum tubes and radios, Philips’ introduced a new type of electric razor, the wildly popular Philishave. (It was invented by lead engineer and fellow Jew Alexandre Horowitz.) During the Holocaust, the family fled to the United States and ran the business from there. One son, Frits Philips, remained behind, and spent several months in an internment camp. He would save the lives of 382 Jews that he employed in his factory, convincing the Nazis that they would assist the war effort. In 1963, Philips introduced the compact audio cassette, revolutionizing the world of music forever. They did it again less then a decade later with the first home video cassette recorder. In the 1980s, Philips developed the LaserDisc, and together with Sony, brought about the age of the CD. Similarly, in 1997 Philips and Sony developed the Blu-ray disc. Today, Philips is still the world’s largest lighting manufacturer, employing over 100,000 people, with revenues of nearly €25 billion. In 2012, Greenpeace ranked Philips first among energy companies and tenth among electronics companies for their green initiatives and commitment to sustainability. This is very much in line with Gerald and Anton Philips’ original vision. The brothers were noted philanthropists, and supported many educational and social programs in their native Netherlands.

Words of the Week

Incidentally, Europe owes the Jews no small thanks for making people think more logically and for establishing cleanlier intellectual habits – nobody more so than the Germans, who are a lamentably déraisonnable race who to this day are still in need of having their “heads washed” first. Wherever the Jews have won influence they have taught men to make finer distinctions, more rigorous inferences, and to write in a more luminous and cleanly fashion; their task was ever to bring a people “to listen to raison.”

– Friedrich Nietzsche

A 1968 Philips audio cassette recorder; a Philips Magnavox video recorder; Philishave rotary razor; and an early LaserDisc player model

Aharon Yehuda Leib Shteinman (1914-2017) was born in what is now the city of Brest, Belarus. To avoid being conscripted into the Polish army, the young yeshiva student fled to Switzerland with some classmates. He continued his diligent studies in a Swiss yeshiva until being arrested during World War II and sent to a labour camp. Shteinman was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust. He settled in Israel after the war. There, the young rabbi quickly made a name for himself as a Torah prodigy, and was soon appointed rosh yeshiva, head of a Torah academy. He would serve as a rosh yeshiva for the next five decades, while also establishing a number of children’s schools for the underprivileged. Meanwhile, Rav Shteinman wrote profusely, authoring dozens of bestselling books and discourses on Torah, Talmud, and Jewish thought, as well as being recognized as an expert in the field of education. While abstaining from politics himself, Rav Shteinman was the spiritual leader of Israel’s Degel HaTorah party, playing an influential role in government. In his 90s, and in frail health, the Rav decided to journey around the world to strengthen Jewish communities. Countless thousands gathered to greet him and hear his wise words in Los Angeles, New York, Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Manchester, Odessa, Berlin, Gibraltar, Paris, and many more small towns. On these trips, he would give as many as 10 talks a day.

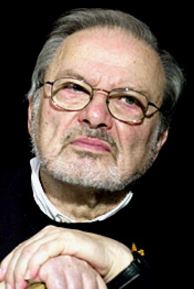

Aharon Yehuda Leib Shteinman (1914-2017) was born in what is now the city of Brest, Belarus. To avoid being conscripted into the Polish army, the young yeshiva student fled to Switzerland with some classmates. He continued his diligent studies in a Swiss yeshiva until being arrested during World War II and sent to a labour camp. Shteinman was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust. He settled in Israel after the war. There, the young rabbi quickly made a name for himself as a Torah prodigy, and was soon appointed rosh yeshiva, head of a Torah academy. He would serve as a rosh yeshiva for the next five decades, while also establishing a number of children’s schools for the underprivileged. Meanwhile, Rav Shteinman wrote profusely, authoring dozens of bestselling books and discourses on Torah, Talmud, and Jewish thought, as well as being recognized as an expert in the field of education. While abstaining from politics himself, Rav Shteinman was the spiritual leader of Israel’s Degel HaTorah party, playing an influential role in government. In his 90s, and in frail health, the Rav decided to journey around the world to strengthen Jewish communities. Countless thousands gathered to greet him and hear his wise words in Los Angeles, New York, Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Manchester, Odessa, Berlin, Gibraltar, Paris, and many more small towns. On these trips, he would give as many as 10 talks a day. Rav Shteinman was known for his extreme piety, humility, and modesty. His daily diet was nothing but a cucumber, a boiled potato, and one small bowl of oatmeal. He lived in a tiny apartment, with little furniture but walls lined end to end with books. He slept on the same thin mattress that was given to Jewish refugees upon arrival in Israel for some 50 years. Streams of people lined up at his open door each day seeking counsel and blessings. Rav Shteinman stood only for truth, even when it brought him adversity. This was particularly clear when he supported the Nachal Charedi, an IDF unit for yeshiva students. Even after some backlash from ultra-Orthodox communities, the Rav stood his ground and continued his support. He was widely recognized as the gadol hador, the world’s chief rabbi. Sadly, the great rabbi passed away yesterday, at 103 years of age. (His condition had turned critical two weeks ago after the tragic death of his 72-year old daughter from a heart attack, even though no one had told him of her passing.) Rav Shteinman wrote in his will that it would suffice to have just ten men to carry out his funeral, and requested no eulogies. Nonetheless, the funeral procession brought over 600,000 people. Israel’s President Reuven Rivlin stated that Rav Shteinman “bore the entire weight of the Jewish people’s existence on his shoulders… he knew how to convey his ideas gently, in a pleasant manner, and with a great love of the Jewish people… He was a man whose wisdom was exceeded only by his humility.”

Rav Shteinman was known for his extreme piety, humility, and modesty. His daily diet was nothing but a cucumber, a boiled potato, and one small bowl of oatmeal. He lived in a tiny apartment, with little furniture but walls lined end to end with books. He slept on the same thin mattress that was given to Jewish refugees upon arrival in Israel for some 50 years. Streams of people lined up at his open door each day seeking counsel and blessings. Rav Shteinman stood only for truth, even when it brought him adversity. This was particularly clear when he supported the Nachal Charedi, an IDF unit for yeshiva students. Even after some backlash from ultra-Orthodox communities, the Rav stood his ground and continued his support. He was widely recognized as the gadol hador, the world’s chief rabbi. Sadly, the great rabbi passed away yesterday, at 103 years of age. (His condition had turned critical two weeks ago after the tragic death of his 72-year old daughter from a heart attack, even though no one had told him of her passing.) Rav Shteinman wrote in his will that it would suffice to have just ten men to carry out his funeral, and requested no eulogies. Nonetheless, the funeral procession brought over 600,000 people. Israel’s President Reuven Rivlin stated that Rav Shteinman “bore the entire weight of the Jewish people’s existence on his shoulders… he knew how to convey his ideas gently, in a pleasant manner, and with a great love of the Jewish people… He was a man whose wisdom was exceeded only by his humility.”

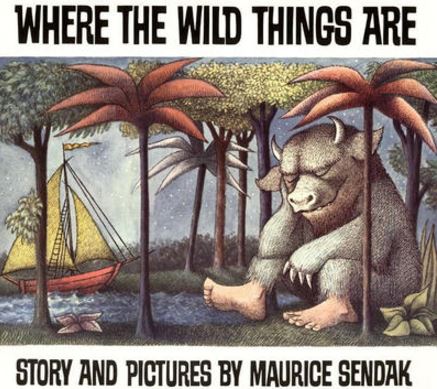

Maurice Bernard Sendak (1928-2012) was born in Brooklyn to Polish-Jewish immigrants. He fell in love with books during a lengthy childhood illness, and after watching Disney’s Fantasia at age 12, decided to become an illustrator. Skipping college, Sendak first did illustrations for toy store windows before having his art published in a textbook. He then devoted himself to illustrating children’s books, including many Jewish themed ones like Good Shabbos Everybody. (Sendak once noted that one of his greatest inspirations was his father’s telling of stories from the Torah.) By the late 1950’s, he started writing his own children’s books. His most famous work came in 1963, and made Sendak a household name. Where the Wild Things Are was very controversial when first published, criticized for its edgy theme and “dark” illustrations. Sendak attributed this to his own difficult childhood, having lost many family members in the Holocaust. Nonetheless, the book became hugely popular, and went on to sell over 20 million copies worldwide. It has since been adapted into a Hollywood film and even an opera, and has been ranked as the best picture book of all time. All in all, Sendak authored 22 books, illustrated 90 more, and wrote, directed, or produced seven films. He saw himself not as a children’s author, but an “author who told the truth about children”. Sendak won many awards, including the National Medal of the Arts, and the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Award for “lasting contribution to children’s literature”. Sendak donated $1 million to New York’s Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, and left his precious collection of over 10,000 artworks, books, and manuscripts to be turned into a museum and library. He was a humble man, and avoided book signings because he “couldn’t stand the thought of parents dragging children to wait in line for hours to see a little old man in thick glasses.” After his passing of a stroke at age 83, The New York Times hailed him as “the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century.”

Maurice Bernard Sendak (1928-2012) was born in Brooklyn to Polish-Jewish immigrants. He fell in love with books during a lengthy childhood illness, and after watching Disney’s Fantasia at age 12, decided to become an illustrator. Skipping college, Sendak first did illustrations for toy store windows before having his art published in a textbook. He then devoted himself to illustrating children’s books, including many Jewish themed ones like Good Shabbos Everybody. (Sendak once noted that one of his greatest inspirations was his father’s telling of stories from the Torah.) By the late 1950’s, he started writing his own children’s books. His most famous work came in 1963, and made Sendak a household name. Where the Wild Things Are was very controversial when first published, criticized for its edgy theme and “dark” illustrations. Sendak attributed this to his own difficult childhood, having lost many family members in the Holocaust. Nonetheless, the book became hugely popular, and went on to sell over 20 million copies worldwide. It has since been adapted into a Hollywood film and even an opera, and has been ranked as the best picture book of all time. All in all, Sendak authored 22 books, illustrated 90 more, and wrote, directed, or produced seven films. He saw himself not as a children’s author, but an “author who told the truth about children”. Sendak won many awards, including the National Medal of the Arts, and the prestigious Hans Christian Andersen Award for “lasting contribution to children’s literature”. Sendak donated $1 million to New York’s Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services, and left his precious collection of over 10,000 artworks, books, and manuscripts to be turned into a museum and library. He was a humble man, and avoided book signings because he “couldn’t stand the thought of parents dragging children to wait in line for hours to see a little old man in thick glasses.” After his passing of a stroke at age 83, The New York Times hailed him as “the most important children’s book artist of the 20th century.”