The Pitbull of Football

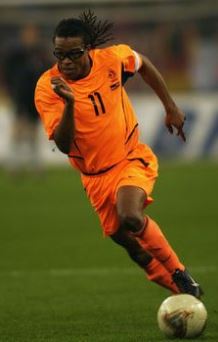

Edgar Steven Davids (b. 1973) was born in Suriname to an African-Surinamese father and a Dutch-Jewish mother. The family moved to the Netherlands when Davids was still a child, and the boy grew up immersed in soccer. By age 12, he signed on with Amsterdam Ajax, a team known for its “Jewish” character. (This is probably due to the team’s origins in pre-war Amsterdam, which had a huge Jewish population and was then nicknamed “Jerusalem of the West”. Today, Amsterdam is still known by the locals as “Mokum” from the Yiddish-Hebrew word meaning “place”). Davids soon led Ajex to three national championships. He also led the team to the finals in several UEFA tournaments. It was while playing for Ajax that he earned his nickname, “the Pitbull”. Davids moved to Italy in 1996 and played for AC Milan and Juventus. His greatest success was in Turin, where he led the team to multiple championships, and was described as a “one-man engine-room”. During this time, he underwent surgery on his right eye (for glaucoma from a previous injury), and henceforth wore his trademark protective glasses. In 2004, he joined Barcelona and immediately changed the team’s fortunes. The struggling club suddenly went on a hot streak, winning all but two games in the rest of the season, and going on to dominate the European football scene for a decade. Davids timely presence has been credited with this huge shift in the club’s history. Davids also played for the Dutch national team in multiple FIFA and Euro Cups, twice being named to the all-star “Team of the Tournament”. In 2002, he was chosen to be one of the stars in a Nike commercial for that year’s FIFA World Cup. The premise of the ad was a “secret tournament” for the world’s “24 elite players”. The video was hugely popular (as was its music, a remix of Elvis’ “A Little Less Conversation”). Towards the end of his career, Davids played in England for Tottenham Hotspur, famous for having a large Jewish fan-base. After a brief stint back in Ajax, he later managed London’s Barnet Football Club, representing an area that is also heavily Jewish. It seems he grew closer to his Jewish roots throughout these years, and once remarked before a big game: “Although I don’t go to synagogue, I will say a little prayer…” In 2004, Davids was ranked among the FIFA 100 World’s Greatest Living Footballers. The 2018 FIFA World Cup kicks off today.

Edgar Steven Davids (b. 1973) was born in Suriname to an African-Surinamese father and a Dutch-Jewish mother. The family moved to the Netherlands when Davids was still a child, and the boy grew up immersed in soccer. By age 12, he signed on with Amsterdam Ajax, a team known for its “Jewish” character. (This is probably due to the team’s origins in pre-war Amsterdam, which had a huge Jewish population and was then nicknamed “Jerusalem of the West”. Today, Amsterdam is still known by the locals as “Mokum” from the Yiddish-Hebrew word meaning “place”). Davids soon led Ajex to three national championships. He also led the team to the finals in several UEFA tournaments. It was while playing for Ajax that he earned his nickname, “the Pitbull”. Davids moved to Italy in 1996 and played for AC Milan and Juventus. His greatest success was in Turin, where he led the team to multiple championships, and was described as a “one-man engine-room”. During this time, he underwent surgery on his right eye (for glaucoma from a previous injury), and henceforth wore his trademark protective glasses. In 2004, he joined Barcelona and immediately changed the team’s fortunes. The struggling club suddenly went on a hot streak, winning all but two games in the rest of the season, and going on to dominate the European football scene for a decade. Davids timely presence has been credited with this huge shift in the club’s history. Davids also played for the Dutch national team in multiple FIFA and Euro Cups, twice being named to the all-star “Team of the Tournament”. In 2002, he was chosen to be one of the stars in a Nike commercial for that year’s FIFA World Cup. The premise of the ad was a “secret tournament” for the world’s “24 elite players”. The video was hugely popular (as was its music, a remix of Elvis’ “A Little Less Conversation”). Towards the end of his career, Davids played in England for Tottenham Hotspur, famous for having a large Jewish fan-base. After a brief stint back in Ajax, he later managed London’s Barnet Football Club, representing an area that is also heavily Jewish. It seems he grew closer to his Jewish roots throughout these years, and once remarked before a big game: “Although I don’t go to synagogue, I will say a little prayer…” In 2004, Davids was ranked among the FIFA 100 World’s Greatest Living Footballers. The 2018 FIFA World Cup kicks off today.

Words of the Week

Most men worry about their own bellies, and other people’s souls, when we all ought to be worried about our own souls, and other people’s bellies.

– Rabbi Israel Salanter (1809-1883)